Friday, April 04, 2014

"Ends Justify the Means" Dilemmas in the Not-for-Profit Workplace

In the not-for-profit and arts world I believe we set ourselves up to be uniquely vulnerable to the pitfalls of ethical systems based on utilitarianism. This is the ethical system in which the "good of the many" always outweighs the "good of the few", a system that becomes challenged when the means are not ethical in and of themselves. In not-for-profit workplaces we think about "Ends" all the time. Right on the top of all our literature and websites we spell out the "Mission". We are focused and passionate about the mission of our organizations, whether it is feeding the hungry, housing the homeless or assuring the survival of a classical orchestra.

Into all this passion and energy for achieving worthy goals comes a number of roadblocks that can make us, as non-profit staff and managers, feel that government funders, sponsors, regulatory bodies, are treating us unfairly, stacking the deck against the success of our organization to achieve our mission. Those challenges include: the preference for funding projects and program costs, over needed support for core operations; shifting priorities and programs from governments and foundation funders; narrow program objectives that don't match the needs of the communities we serve. And some days we feel like if we hear the word "innovation" one more time, we'll scream. We twist our programs pretzel shaped to try to qualify for those innovation grants when, really, we think that the way we have always done things is probably pretty soundly based on best practices.

Between the passion to do good and the frustration about roadblocks that seem illogical, unpredictable and insurmountable there sneaks in a philosophy of the "end justifies the means". Whether we bend the truth a little bit in our funding application to make our planned activity seem like a better fit, or we move expenses in accounting lines to shift expense from administration to program and marketing, we are embarked on a slippery slope. Tensions mount in organizations when doing whatever it takes to get or keep funding pushes staff members beyond their comfort levels.

These are not victimless crimes. Public dollars, the reputations and health of workers, the continuation of programs and services that the public counts on are jeopardized when organizations foster a culture of unethical expediency. Staff members feel helpless in organizations where they are not just asked but required to do unethical things: back-date mail machines to send in applications after funding deadlines, forge a signature because someone is unavailable, spend all their time working on one project that they are not funded to work on and neglect the work they are funded to do (a common way of shifting funds from one program to the other surreptitiously), directly shift funds from one program to another without the funder's knowledge, invent statistics, report fundraising costs of a special event fundraiser as a "program" cost, report expenses of one project as the expenses of another, double and triple raise project revenues for one pet project while reporting a reasonable budget in each request, over-spending ridiculously on one area. . . all things that have been sanctioned in organizations I have worked for in the past. Yet there is little over-sight of non-profits and whistle-blowers at the staff level often have their careers ruined while they sometimes see the non-profit manager who forced the questionable or outright disgraceful practices be backed up by non-profit boards and even to be recognized with national awards.

Any solutions have to deal with both the problem and its causes. Adequate funding of basic operations of non-profits that are operating effectively in the public good will stop the need to fudge program costs to cover operations. I could say that Boards should stop propping up corrupt leaders but . . . that's not going to happen. The "friends of X" board is alive and well everywhere. I have come to the conclusion that there needs to be tougher regulatory bodies at the provincial and federal level that will investigate allegations of mismanagement of publicly funded non-profits. Working currently in a very well-managed and ethical non-profit has given me new perspective on the harm that unethical non-profits do to workers, funders and programs.

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Writing Grant Proposals as a Team

Grantwriting in a Team Environment

Grants written with a collaborative team are usually stronger, more realistic and tied to the real activities and history of the organization and provide opportunities for team-building. Grants written with a collaborative team can also be among the most frustrating and time-wasting of activities if there is no plan for the collaboration and team members don’t adequately understand their roles.

Why write a grant collaboratively?- Capitalize on multiple talents

- Get multiple viewpoints

- Increase organizational and/or partnership buy in to the project proposal

- Define roles

- Choose the team

- Chart a realistic timeline

- Choose tools

TEAM ROLES:

NOTE: Many times one individual is responsible for more than one role in grantwriting, but it is useful to break down the roles to understand all areas of responsibility. For most grants the roles include:

1. The Grant Lead: This is the person, often referred to as “the grant developer” who is delegated responsibility for team leadership on the grant. They define the process, assign grant tasks, manage the timeline and are ultimately responsible for declaring when grant components are final. They may or may not be the actual grant-writer.

2. Grant Researcher: This role requires someone with skills and experience in researching funding bodies and (if applicable) expertise with the fundraising database used by your organization. They identify funding programs with high relevance to the activities of the organization.

3. The Grant Analyst: This role requires someone able to summarize the grant requirements and provide the information to key individuals within the organization for decision-making about whether and how to proceed and to set out key requirements needed to be met (such as signed contracts).

4. The Organizational Historian/Fact-checker: This role provides up to date content on organizational history, mission, projects, as well as needed documents such as board lists, audited financial statements, incorporation papers, photos, biographies/profiles of team members and partner organizations.

5. The Needs Manager/Project Rationale Researcher: This role is able to research the “need” that the project addresses whether it is a need in the community or an organizational need. Articulating the need is important to making a case for the relevance of your project (whether the application asks you to answer questions about needs or not).

6. The Grant Writer: This is the individual who takes all content provided and crafts it into a coherent argument that is presented with one voice through the document. They are ultimately responsible for style, grammar, format.

7. The Collaboration Organizer: This role is responsible for the nitty-gritty of the collaborative effort, sending invitations to team members, organizing meetings according to time-line, chasing people for content, and tracking the receipt of all needed materials, signatures, support letters, etc.

THE GRANTWRITING TEAM:

While above, I have defined the ROLES needed within a grant-writing process, one team member will likely assume more than one of the roles. Your grantwriting team may be 2 people or 20 people (or more). Most grants involve 2-4 key contributors with some input from stakeholders. Who you choose for your team depends on your organization and the nature of the application. While you typically would want only one person assigned to some roles (such as project leader and/or lead writer), others can be performed by teams (such as researching community needs or literature surveys, getting equipment quotes).

KEY SKILLS:

The skills you need to assure are on your team include:

1. A professional within the organization who has key insight in the organization’s history, goals, and able to speak to the nature and importance of the key points of the proposal.

2. A grantwriting professional who is skilled in researching funding opportunities in tune with organizational needs

3. A budget specialist able to craft a realistic project budget and answer financial questions about organizational finances

4. Writer/editor who will be the “voice” of the grant--responsible for the tone, grammar and persuasive language of the grant

Unless one person has ALL of the skills above, you need to develop a team however small! If you are the Grant Lead--taking into account both the roles needed in the grant and the list of key skills--consider who will make up your team. Following the rules for good delegation, you will need to assure that team members understand their role(s) on the team as well as the role of others. Each team member must have the tools and resources needed to perform the tasks (time, materials, budget) and the authority (existing or clearly delegated) to successfully fulfill their role.

TIMELINE:

Chart your timelines with key points for completion of stages of grant development through a work back schedule from the due date with full understanding of that due date which can vary from “postmarked by X date” to “must be in our hands by 5 pm on the due date”. While generally the earlier the better, a too early start date can undermine any sense of urgency about the work and lead to procrastination and dropped balls. Likewise some RFP have tight timelines that mean that intensive work will be unavoidable.

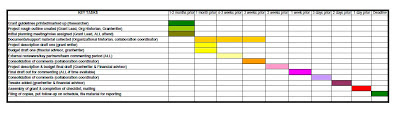

Generally the charting done by an experienced Grant Lead will look like this:

By making your first draft completion date far enough in advance, you can allow for a second round of commenting and revision if necessary or if the project gets behind schedule due to external factors or difficulties in obtaining all information needed, you can forgo this step.

TOOLS FOR COLLABORATION:

Do you need special tools for collaboration? Not necessarily. It depends on your team, process and proximity. If a grant is being written by one person who edits submitted content and incorporates 2-3 team members content and comments (the majority of grant-writing scenarios) no special tools are needed. Emails, word documents or notes written on a table napkin, will all be incorporated by one individual into a master document that is not available for editing by anyone else. No tools beyond a word processor needed.

Where it gets dicey is where multiple individuals are working on writing/editing sections of the grant collaboratively (and there has to be a strong rationale for this approach). Here version management becomes difficult and if there is no system in place, valuable content can be erased by a contributor who lacks the big picture. The grantwriter has started by organizing content into paragraphs dedicated to single ideas, ensuring that all building blocks are in place over the entirety of the grant. This can become lost as new writers add irrelevant details to paragraphs unaware those ideas are stated later, or in a different section of the application that they may not have in front of them. Simply tracking the revisions becomes a chore. Take this as an example: Susan has written the first draft of a project timeline that outlines a series of workshops. She sends it out simultaneously to Sandra and Kevin by email. Sandra gets back to Susan first with her revision and has added 2 workshops to the list. Kevin (working on the original document) adds one workshop. If Susan saves the most recent edit (Kevin’s) as final, she will not have incorporated Sandra’s input. So how will this be avoided without adding hours of pouring over revisions with a fine tooth-comb?

The need for a unified voice and coherence within the full application dictates that:

- The process for editing needs to be clearly articulated

- There needs to be a start and end point to edits (a date where no more edits will be received and the key writer will consolidate).

- A system or tool for tracking versions must be decided on and used by all contributers

- The final edit must be done by one person assuring a single voice and coherent thread.

MS Word “Track Changes”:

When two or three editors work on a document and only one or two revisions are anticipated, the tools within Word for tracking changes, emailed back and forth will likely be sufficient to the team’s needs, provided they agree on version labeling and documents are not sent to multiple editors at one time without the knowledge of the key writer. The key writer needs to know which version of the document the edit is based on to not lose content previously submitted.

The drawback of “track changes” with multiple edits and editors is that the document becomes unreadable unless the revisions are hidden by selecting “show final”, however in that view content crossed out by one editor which may be necessary and need to be restored can be lost.

Google Docs

Google docs are similar to MS Word’s track changes in look and feel. The advantage of using Google docs is that two people cannot work on the document at the same time so that the most recently saved document is always based upon the work of all previous contributors.

Wikis

Wikis were developed specifically for collaborative writing and allow team-members to look at all version histories. Within a wiki, it is easy to roll back to a prior version or ensure content is not lost. There are a number of free wiki spaces available online and using wiki tools are highly recommended where team-writing for sections of a grant involve three or more people and or is anticipated to involve more than two rounds of editing. My favorite wiki spaces include: http://www.wikispaces.com/ and http://pbworks.com/

Proximity (a collaborative tool we sometimes forget):

Grant-writing teams seldom go off the rails when collaborators work in the same office space and work the same days/shifts. When they do not, it is important to be able to simulate the good synergy effects of proximity. Wiki tools help with this. Meetings, web conferencing, shared Skype calls, and even meeting virtually in online environments can avoid the pitfalls that occur when collaborators feel they are working in a vacuum at some points and are surprised by input from other team members at other points.

Symptoms of failed collaborative grantwriting:

Reluctance to contribute in a timely fashion: One of the leading signs of a process that is failing is the hording of information and avoidance of content sharing until the last moment of a grant deadline. People do this as a defense when they feel that earlier input will be lost or be subject to so many revisions that it will add to the time they will actually be required to spend on grant-writing. "Why contribute now, it will only have to re-done 10 times?"

Lost or confused content: Editors are simultaneously working on the same document making tracking versions difficult to impossible. "I'm sure we had something in here about X in an earlier version. Where did it go?" The wrong tools are being used for collaborative writing.

Surprises and conflicts: "Why are you working on X? I've already done it!" The team and roles were not clearly defined.

Loss of engagement by project and/or writing lead: You send your lead writer comments and edits galore and they stop responding. There's likely a timeline problem. The editing process needs to have a clear end-point so that final draft can be constructed. Grantwriters who are unsure of when they are needed for final edits may be reluctant to contribute until they are sure the dust has settled to avoid wasting their time.

Lack of consistent voice and format in final grant: Editing and commenting has not been terminated with enough time for grantwriter to polish and format or grantwriter has not been correctly delegated authority to override edits that are off message.

Lastly take this quiz

- We always have organizational buy-in for our grant-writing before we begin. Yes/No

- Our grant team all know their own roles and responsibilities. Yes/No

- All team members know from the outset who will contributing and how. Yes/No

- Our grant process has a defined time-line for key steps. Yes/No

- Our tools match the number of collaborators we are involving. Yes/No

- We work in close proximity or have plans for meeting/conferencing as needed. Yes/No

- We have no difficulty tracking revisions to grants. Yes/No

- We are never surprised at the last minute by missing documentation or signatures. Yes/No

- Team members contribute on schedule with confidence their input will not be lost. Yes/No

- Grant proposals have a unified voice and a coherent argument on completion. Yes/No

SCORING:

Give yourself a point for all your “yes” answers.

A perfect 10: Where do I apply to work for you as a grant-writer? Great going.

7 to 9: You are like most organizations, doing most things correctly but there’s probably just one area where you could avoid conflict and time wasting if you planned a little better.

4 to 6: You are probably experiencing some staff stress or even conflict. You may be wasting time and energy due to duplication of work by people not understanding their roles and/or doing intensive last-minute grant-writing due to lack of pacing.

Less than 4: Grant-writing collaboratively is either very new to your organization or has become a huge trial that your staff members view with dread. They react with either avoidance/delay strategies or by jockeying for position when a grant-writing task is announced. The process is likely always contentious and the results are worse than if one person completes the grant leading you to feel it is better you do it yourself. (Most of us have been there.) Consider, if you feel this way, whether your team really lacks the skills or whether the process is at fault.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Metropolitan Opera Company breaks fundraising record

In arts offices around the world, questions are being asked about this outcome. Is this an endorsement for the Metropolitan Opera's revolutionary electronic distribution in theatres; a vote of confidence for their current artistic direction; or simply the effect of donor behaviour--backing core arts groups in hard times?One major donor David Knott agrees with the electronic distribution policy saying it was a decision that "if we can't bring people to the opera, let's bring opera to the people". He put his money where his mouth was in making a $500,000 one-time gift and pledging a bequest to the company through it's planned giving program. Electronic distribution certainly seems to be a way to follow the market. In its 2003 study "The Magic of Music", the Knight Foundation found that while 60% of Americans listened to classical music, only 5% had ever entered a concert hall. Listening to classical music is not declining, going to concert halls is declining. Smart, business-minded donors like David Knott will be more inclined to invest in arts organizations that make decisions soundly based on audience trends, it would seem.

In a time when 2 out of 3 arts organizations have sustained a decline in income, the phenomenal success of the Metropolitan Opera in increasing its donations has to be seen as tied to the most significant new part of its program, the electronic distribution of opera in theatres. This fact should be an encouragement to those trying to pioneer new methods of distribution and electronic outreach initiatives. From my own work in virtual music, I know that resistance to new forms of distribution seems like a brick wall at times, but smart donors are rewarding those arts organizations bold enough to break through to reach their audiences outside the concert hall.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

US survey shows grantmaking fell 8.4% in 2009

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Good deeds with denim

Great idea!

Wednesday, July 01, 2009

Canadian Corporations vow to continue charitable support

Many companies suggested that their multi-year commitments meant that they had an inability to do much to respond to new requests for funding. At the same time companies report many more new requests coming across their desks as charities feel the pinch.

Austere times have meant a shift in priorities for corporations. Galas are going to find it more difficult to sell corporate tables as company heads find it difficult to justify thousands for black tie dinners when they are laying off staff and the charitable needs of healthcare, housing and poverty relief are in the news daily. Many charities are responding with changing their fundraising events or radically scaling them back.

Arts, culture and sports will be the losers as corporations continue to migrate funding to education, healthcare, and community programs.

Accountability is a key word in corporate funding these days. Corporations are selecting priority areas for their charitable dollars and now more than ever, projects seeking funding need to demonstrate how their activities are a fit with corporate goals. Reporting back to the funders on the reach of their corporate dollars--while always an important step in fundraising--is not an absolute requirement for ever being funded again by the corporation.

The 7 tips for non-profits in tough times is well worth reading this small quarterly.

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Grantwriting Basics -- Grantwriting 101

Since the bulk of my grantwriting has been in the Canadian arts--where I have to assume a type of applicant and type of funder--that will be the basis of my examples.

Corporate fundraising uses some of these same techniques but as it is substantially a different process than grantwriting, it will not be explicitly covered in this article. Corporate foundations, on the other hand are foundations and should be handled as a part of your foundation campaign.

IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL FUNDERS

Know your government funders and programs: If you are an arts or non-profit management professional, you likely already know the major funders for your program activities. In the arts at the national level you will be researching programs primarily from Canada Council and Heritage Canada. (From time to time other departments offer programs for foreign travel, international marketing of arts events.) Provincially, you will be looking at provincial arts councils and tourism programs that are available to support marketing for cultural events. Municipally or regionally, you will be looking at the programs of civic, regional, or county arts councils and regional/local tourism initiatives. Don't be afraid to call the Officers administering the programs to ask what programs fit your activities. Book a meeting with them if you are a new grantwriter, or new to the discipline, organization or geographic area. You may learn about programs that fit your planned activities that you didn't spot on the website, or in the literature. Establishing a good relationship with your Grants Officer is a really important first step in grantwriting for an organization.

Subscription databases: If you can afford them and you don't have a good list of funder contacts in your organizational records, you may want to subscribe to one of the subscription databases that are out there. They are expensive but it will only take one additional foundation grant that you would not have received to pay for the Bigonline database or Foundation Search Canada . Even one year of a subscription database will help you build your list of funders to the point where you may not need this resource in future years if cost is an issue. Note that these resources are not without some errors. I have found that where my organization has had an active relationship with a foundation, I have often had more accurate information regarding contacts, programs or even contact information changes. Building and maintaining your own contact list geared to your own program relationships/fits is irreplaceable.

Public tax information of charitable foundations: Okay, you can't afford an online database but you don't have much of a list of past donors in your organization. In fact the most recent foundation files are dated 1999? Sigh. I have so been there and done that. My commisserations!

Here is a real tip. Foundations are in themselves charities. As such they have to file a charitable information return with Canada Revenue. And that return is available to you free ONLINE. You can search the name of any foundation you are interested in, or search on a search term like "Foundation", or by city, to net yourself a list to browse through. You can open up the information to see who is on the Foundation's board and which organizations they have given to in the year of the return.

See below a screen shot of a search on all private foundations in Ontario sorted by city. All those with icons of returns on the right have accessible returns.

Buried deep within the return you will find a list of the projects and organizations funded by the foundation and the amount of each grant. This, together with the listed mission of the foundation, will give you a strong indication about whether this foundation is a fit for your programs and also what level your ask should be at for a program such as yours.

Buried deep within the return you will find a list of the projects and organizations funded by the foundation and the amount of each grant. This, together with the listed mission of the foundation, will give you a strong indication about whether this foundation is a fit for your programs and also what level your ask should be at for a program such as yours.

Finally access the foundation contact information of those foundations who fit and add that contact and any other information about website, deadlines, application forms and process to your grantwriting calendar.

Search public and foundation funders of projects like yours: You know who your competition is, who your colleagues are in the community and in neighbouring communities, and a little skill with online search engines and you are able to come up with some unique search terms that will generate a list of programs and services like your own. When you see a pattern of funding projects like your own, pull out all the stops to track that foundation or charitable giving program down. These are key funders with high probability of success.

Don't forget local family foundations: Sometimes we overlook family foundations in our neighbourhoods who may not have a discernible pattern of giving to projects like our own. That is because their giving is focused on all quality of life projects IN OUR BACKYARD. They give a little bit to fitness, some to amateur sport and some to education. If we are looking for "arts funding", we may never find them. However as the local symphony or community arts organization in their community of interest, we fit solidly within the mandate of their foundation and they want to support us! Don't deny them the chance to give us their money.

PREPARING ORGANIZATIONAL AND PROJECT PROFILES: Annually when your next season is well advanced in planning and before the first major operational grants are due, it is a good practice to update Organizational and Project profiles. This main document will be used in the following ways:

- As is for press-release backgrounders, potential board members, foundation appeals to foundations that lack a set process, as backgrounders to foundation appeals with more targeted content in the main application.

- Tweaked for foundation appeals where the emphasis is on an aspect of the program, expanding some sections, condensing or omitting irrelevant content

- As fodder to cut and paste into relevant sections of government grant applications and into the application forms for those increasing numbers of foundations that have a formal application process.

- Mission, Incorporation date and charitable number--if you have a briefer version of your Mission, you may want to use it here.

- Brief history of the organization (updated, brief, and engaging)--focus on accomplishments, programs, community impact, staying away from tedious details that are of internal archival interest only. Quotes are great!

- Artistic or Leadership statement--Put a photo of your conductor or theatre artistic director beside their own words on what is exciting and valuable about your upcoming program. Don't under-estimate the ability of Artistic Leaders to frame the importance of their work. If they won't write something for you, give them a phone call, write down what they said and send it to them for approval. It will help you as a grantwriter. You may be looking at a season that looks like a hodge-podge. You have no "hook" to hang your thoughts on, but when the Artistic Director tells you the season is a "dialogue between the conventional and the new, the audience's taste and the pressure for artistic innovation"... wow... you are off and running with and angle for your prose.

- Main Program Description--Describe your artistic season or core programs. While you might start with brochure content here, don't stop there. You want to think always from the standpoint of impact. What are the benefits to the community, artists, the art form, ties to education or multiculturalism in your program? How is this program a stretch for your organization, or the artists in your orchestra?

- Community Outreach/Education and/or Adjunct Programs--separately describe your audience development and outreach programs. Start with and update the descriptions of annual and recurring programs. Next add what is special and unique about this years programs and share details of one-time programs. Illustrate your content with examples and photos from last year's successful programs. Include participant's quotes. Their words are always going to include more weight than yours, no matter how hot-shot you think you are as a grantwriter!

- Organization--Who are the key players? Brief bios of artistic leadership and management here. Organizational challenges and triumphs. Any major projects in the coming year. (A Board List will accompany where appropriate).

- Financial Position of the Company--If you have a debt, here's where you explain it. If you have a surplus, here's where you explain why it is needed and why it can't be used for operating. Do you need to save to repair the roof next year, or are you on a cycle with a festival every two years? This is only a good news over-view, you'll need a detailed explanation for funders if you have serious explaining to do. (You'll attach financial statements where needed).

- In addition to your main project description prepare single sheets for specific adjunct and optional projects. Are you going to have two composers visit schools next year? Prepare a "Composers in the Classroom" page. Are you going to have musicians from your orchestra give workshops? Prepare a "Young performers workshops" page. Are amateur ensembles going to play before your concerts? Prepare a "Community Overtures" page.

- Update or create project pages from the former years projects. If you had a successful collaboration with a youth choir last season, do a one-sheeter on it.

- Try to keep your project titles consistent as that will allow you to send three sheets on "Young Artist Spotlight" that detail past and planned activities. Although the activities may have slightly different aspects, the one linking idea--in this example, young artists on the stage--will allow you to build a case for this stream of activity within your organization.

- Targetted foundation and corporate appeals

- Reports to donors on prior projects funded

- Fodder for larger applications

- To add to or tweak applications to foundations where added emphasis is needed to match the funder's priorities or mission.

- You can use MS Outlook, a database, or a spreadsheet to construct an annual calendar for you to chart the deadlines and progress of your grantwriting.

- Be sure to keep and include your accumulated knowledge arising from your past successes and failures with the funding body. Many funders ask you when you applied to them last, what for and what was the result.

- As you talk to officers, look at websites, add all information into your grant calendar listing. Link to application forms and guidelines where those exist.

- Where deadlines are given, you can enter those along with your own projections of when to schedule work on this grant. Many foundations will give vague information such as "meet before the end of each fiscal quarter". You will have to either find out the deadline or plan to have the application in well before the deadline might be anticipated to fall.

- You will determine patterns in your calendar which will allow you to schedule grantwriting weeks where you will lock the doors, turn off the phones for some part of the days and focus on a series of foundation appeals or a major operating grant. In my experience, given basic knowledge and writing skill, the major determiner of a successful grant is the time invested.

"Team, what team?" you ask. I smile as I have certainly written many grant applications on my own. However, there are ways to divide up the tasks to work with one or two other staff members in assembling materials for your more major grant applications. Even if it is only you on your lonesome, it may be helpful to you to think of working on your grant applications in terms of these tasks which may be extracted and assigned.

- Pre-read grant application forms, program guideline sheets AND final checklists, making a list of everything you will need for the grant. Please note that due to over-sight, omission or sadism, there will often be some item that you cannot get at the last minute which will only appear on one of three of these documents, usually the final checklist. If you only look at that as you prepare to mail your application, you will be up a creek without a paddle. Be sure you have defined the deadline properly: is it "postmarked by X date", "in our office before 5 pm on X date", or "in our office before midnight on X date".

- Solicit, acquire and create a file of all needed external and internal documents: These can depending on the program include: financial quotes on equipment you are intending to purchase with grant funds, artistic statements from artistic leaders, signed releases from creative partners, signed Motions of the Board authorizing the application, copies of Letters of Incorporation, signed Financial Statements, work samples on CD's, copies of scores, letters from references, marketing materials, marketing plans from companies on retainer, resumes of partners, etc. You will want to chart progress on these items to avoid nasty surprises.

- Create an electronic "fodder" file: On your computer network create a folder into which you throw copies of all documents likely to be of use to you during the grantwriting process. (You will delete these copies later). This will save you oodles of time in searching and opening and re-opening the same documents as you look for re-useable content. These documents will include your organizational profile, individual program sheets/descriptions. Strategic planning documents. Past grant application to the same government body. Recent grant application to other government bodies. Documents on financial planning. Statistics, budgets, and copies of marketing materials.

- Fill in grant cover sheet (get signatures done well in advance).

- Create separate documents for your main prose sections for the application.

- Cut and Paste--Use your current organizational profile and any other relevant content in your fodder file. Do a rough cut and paste of the material into the program sections where it best fits and might be helpful. Do not worry at this point about duplication. You are merely positioning the material for convenient accessibility.

- Statistics and Budget pages: Do these as fully as possible before starting on the prose. You can cut the time you spend on editing prose a lot more easily than truncating the time on stats sheets and Budgets. Trends evidenced in these sheets will help frame the prose.

- Write and edit. Self-explanatory as this seems, determine well in advance who the lead writer is and who gets to say, "this is done". Arguments on these points seem to happen frequently in mid-sized to larger organizations and make a tense process much worse.

- Proofread.

- Make the required number of copies and prepare as required

- Checklist of everything submitted

- Copy to file.

- Cover letter

- Mail, courier or hand-deliver. Nothing quite compares with the festive atmosphere in the line-up at the last post-office open in a major city on the deadline of a major grant. It is a time to meet old colleagues and catch up with the news from last year. But really, we'd much prefer to have been home at 5 pm rather than be in a post office at 10 minutes to 10 pm.

- Make a plan: List everything you want to tell the funder in brief points.

- Make it easy for them to give you the money by using their language. In addition to the application forms and guidelines that shape your writing, be sure to take time to read annual reports, strategic planning and online copy from your potential funding body. As you read, highlight (or electronically extract if possible) the prose in their documents that resonate powerfully with what you do or are proposing. Put this in your "fodder" file. Organizing your argument under sub-headings that echo their goals and priorities, using their language makes it easy for funders to see where your activities and plans fit their funding priorities. I worked with one great grantwriter who called this, "finding the money words".

- Tell your positive story first. Find several key points in each section that are strong positives. Put them upfront and in strong brief language. Use quotes from stakeholders, partners and leaders to enliven and add credibility.

- Address negatives briefly and honestly - move quickly to your positive plans (the only exception to this is applications for organizational effectiveness projects where you are making a case for the needs of your org.)

- Keep to length guidelines: Find out how flexible your funding body is in length guidelines. If they have some flexibility, don't abuse them. Sometimes copy from one question might be adapted and moved to another question that allows for a more lengthy response.

- Have you hit all your high notes? Look back at your list from No. 1. In your edits and moving blocks of copy around have you failed to tell some of your positive stories? See where you can fit those missed notes back in.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS:

- Be honest: Any dishonesty or misrepresentation in your application will assure you have a very short relationship with the funder, so you want to be sure that you'll deliver on everything you have outlined. Fudging on postage dates is mail fraud, unfair to your colleagues and creates a nasty, unethical climate in organizations where leaders coerce staff into going along with submitting applications days after deadline with an old postage meter label. Expose this where it occurs. If extensions are needed due to dire circumstances, often there is a way to submit a barebones application with additional material coming as updates.

- Don't forget to file your reports. A part of successful grantwriting is filing reports as required. Since you are reporting on last year's activities anyway, send reports even to those funders that don't require them.

- Recognize your funders: assure that funders have the logo recognition and thanks that meets or exceeds the funder's expectations. Forgetting the Canada Council logo on your program book today, means you will not want to send that program to them with your next application, no matter how good it looks. When logos and thanks are part of your development team plan, meeting your final requirements and giving courteous acknowledgement is assured

Monday, October 29, 2007

Restoring trust in the charitable sector.

If the recently announced self-governing code of ethics proposed by Imagine Canada is not enough to restore confidence in the transparency of the Canadian charitable sector—and I don’t believe it is--what additional steps could realistically be taken?

Set fair guidelines for administrative and fundraising costs varied by sector and type of charity:

The first step that everyone seems to miss is that we need to establish what is a fair expectation of the percentage of funds needed for administration and fundraising. No non-profit can function without paying the rent, insurance, office supplies and staff salaries. And to be fair, it has to be noted that the percentage of the budget spent on administration and fundraising can vary widely in different charitable sectors. We want to remove any excuse for obfuscation in reporting by allowing adequate costs for legitimate administration and fundraising costs. Consider these two scenarios:

Charity A runs musical after-school activities for children. The charity has one paid staff member who does grant-writing, foundation appeals and writes letters to private donors for donations to support the work of the program. The bulk of the staff members time is spent in organizing the programs, contacting schools, preparing program materials. The charity operates out of donated school space. Less than 20% of the charitable organizations budget is spent on administration and fundraising.

Charity B exists to organize one annual high profile special event to raise money for a health related charitable purpose. Special Event fundraising is the most expensive method of fundraising. All of Charity B's staff are involved in fundraising and organizing the charitable fundraising event itself. Charity B provides no direct charitable programming but transfers profits to charitable organizations that do. In a good year, the large fundraiser realizes 40% profits on the investment in the event. In a bad year, only 20% may be available for transfer. Arguably it may be money that could not be obtained any other way.

These are extreme examples of the apples and oranges that make up the charitable sector. Too often unrealistic goals of lean administration and fundraising costs are expected by donors, foundations and government programs, without any consideration of sectoral differences or other factors affecting a non-profit corporations real costs. These unrealistic expectations by some funders leads to a certain climate of obfuscation in the charitable sector. If a good organizational leader knows that showing an administration cost low enough to qualify for project support is impossible, she/he will naturally think of ways of funding the extra very real administrative costs from another program. The administrator thinks “it’s all in a good cause”. Volunteer Boards become used to hearing that we have to “rob from Peter to pay Paul” because the portion allocated to be spent on administration and fundraising is just too low. And Boards will be tempted to think "everyone's doing it". In such an atmosphere it becomes hard to draw the line and know just what are the real programming expenses and just how high is your fundraising and administrative costs.

Funding bodies, sectoral umbrella/advocacy groups, and non-profit administrators have to come clean with each other and set realistic standards for administrative and fundraising costs in order to set realistic benchmarks that organizations can then measure themselves by going forward.

Introduce standardized accounting systems that are geared to non-profit management

If it is all about the numbers, then how we count and what we count becomes very important.

Current systems of accounting only make donors aware of the hard dollar costs and benefits of non-profits without offering any other tangible cost/benefit analysis. There are some huge misses as a result. One of the most obvious is the benefit to the community when huge groups of volunteers are involved in a charitable activity. The volunteers benefit in training and a sense of well-being. They take skills back to their jobs and communities. Their work gives huge benefits to the charity whom they work for. Conversely what are the costs when a non-profit turns over its full staff almost annually because of poor management? Donors are funding unnecessary staff training and potential law suits when human resources practices are below par. But that’s not on the balance sheet either. A charity that is creating great work in the community with a mainly volunteer force supervised by a few paid workers may look identical on the books with a floundering charity with the same number of staff and little real activity.

We also need standard accounting practices to separate project versus operating expenses because so many of us are paying operating expenses out of portions of project funds. This is a legitimate practice when a number of project budgets have small amounts of administrative costs factored in. Keeping track of what is allowable becomes complicated as number of project streams increases. Having worked in one charity where large sums of project funds were allocated to administrative and fundraising costs, while being posted as program costs, I have seen that it can be done without ringing alarm bells at audit time.

Professor Jack Quarter, at the Ontario Institute of Studies in Education, Social Economy Centre, has been doing some ground-breaking work on Social Accounting that should prove useful in any initiative to restore public trust in our charitable sector.

Once new non-profit accounting standards are adopted it will be necessary to communicate these new standards through professional accounting bodies to assure that accountants, bookkeepers and auditors are aware of the new practices.

Accounting professionals to be held accountable

When things go off the rails in the corporate world, everyone looks to the corporate auditors. How did they miss this? Was there collusion? Should the auditing firm be punished?

But does this happen when it is disclosed that charitable funds have been misallocated to admin and fundraising in charitable institutions? Why not?

In the past I have attempted to make an auditor aware of deceptive practices in an organization I was employed by and was frozen out. I reported the auditor and the Board Treasurer ( a chartered accountant) to their professional regulating organization and got no response. Why? The rationale I received was that they were volunteers or working below the usual fee, doing a good deed, and therefore couldn’t be expected to give the due diligence of a professional accounting job. This didn’t strike me then or now as acceptable.

Should accounting professionals be held accountable when private donations and public charitable funds are misused? That’s a question for the profession and the public to consider.

Sharing of information among charitable funders

Currently in researching information about a charitable institution you can find their charitable return information online which gives you broad categories of where they receive their funding from. You can also access information from some of the big foundations and government programs and discover the size of their program contributions to the charity.

What you can’t find out and what isn’t shared between funding bodies is what they have actually funded. This results in charities being able to double-fund activities and staff salaries with impunity while channelling the dollars into those administrative costs and fundraising costs that they really don’t want to report.

More information has to be publically available.

Volunteer Board Training and Information

In theory all non-profits and charities are governed by a volunteer Board of Directors who exercise a stewardship function within the organization. In actual practice, the Board is often comprised of very busy people with good hearts who really want to believe that their charity is doing the good job. Most of the time they are right.

Unfortunately, the main source of information and training on Board functions is often a non-profit manager who could have a vested interest in making the charity look more successful than it is. Boards need some measure of independence and Board members really need training and information on charitable standards of business practice that comes at least in part from somewhere outside their organization. As all charities have to provide a list of Directors as part of their annual information return, Revenue Canada could serve as a source to send all Directors a regular update on industry standards and provide the means for Board Members to be alerted to the tell tale signs that something might not be quite right in their organization.

Providing Disincentives for Breaking Ethical Standards

There are currently few mechanisms in place to deal with organizations that break existing ethical standards in raising charitable funds or who misallocate charitable funds. While it may be difficult for the small donor to trace the use of their funds, the same is not true of government programs that make tax dollars available for charities. When a public funder discovers a major breach of ethics, there should be repercussions and disclosure.

It is in the interests of all ethical and hard-working charities to see charitable licenses revoked for those that don’t play by the rules and contribute little or no social good.

Whistle-blowers

Almost everyone who has worked in the charitable and non-profit sector has had at least one horror story about unethical practices. Most never get reported. One simple reason is that there simply is no one to report the situation to outside of the organization’s own Board of Directors. Plus there is a lot of pressure to disregard the accounting irregularities on an “ends justifies the means” argument. Employees who take the step of going to the Board can find themselves jobless and without a reference, often not listened to at all. I know of one instance where a loyal staff member stealed themselves to take a troubling set of facts to a Board Member. The next day the manager came to her office and said, "Everything you tell a Board Member will come back to me in a few hours and if you ever do this again you will be fired and you will never get a job in this sector again." Even when groups of staff go to Boards of Directors, they are often simply labelled troublemakers. One of the first things a non-profit manager with something to hide does is try to isolate the Board from the Staff and discredit any staff member who might have knowledge of misdeeds. Boards should be highly suspicious of managers who inform them that direct communications between organization staff and Board is “inappropriate”. After seeing this suppression of staff in organizations I’ve worked with in the past, I’ve come to the conclusion that we need a Canadian tip line for charitable and non-profit wrong-doing and whistle-blowers need protection from reprisals in the workplace. We can’t solely depend on over-worked, under-informed volunteer Board members. Imagine Canada has taken the lead in formulating a new ethical standard for charities. They may the be the logical body to administer a tip line on charitable fraud and other unethical practices.

With all these steps in place, we can establish what the standards are, communicate those standards and weed out the few bad apples. The result will be restored public trust, an end to misallocation of charitable dollars, and a better working climate for some of the most idealistic and selfless workers in the Canadian workforce.

Self-policing code of ethics for Canada's charitable sector announced

In the wake of exposes by the Toronto Star of fundraising practices by some charities that have resulted in as much as 90% of funds raised going to fundraising and administrative costs rather than charitable work, the charitable sector has announced the implementation of a self-policing code, reported in the October 22/07 Toronto Star story, “Charities Launch self-policing code” by Kevin Donovan. (note that link is time sensitive)

Is it enough?

The public is worried about donating wisely and--on the other hand-- those of us that work in the non-profit, charitable sector understand that the problem of getting the most bang for the charitable buck is deeper and more complex than the simple solutions suggested as first steps. We have some idea of where the bodies are buried.

The frustrating thing for those of us working in the sector is when we see a great program working very effectively in a sector fail to gain support, while a noisy charity that really does very little beyond generate hoopla and organize fundraising events, gets media attention, celebrity support and commands public dollars.

Through Imagine Canada, charities are being asked to sign a voluntary code. One of the first provisions of the new code is that signators will not use commission fundraisers as this practice can lead to both aggressive marketing and the use of charitable funds to simply pay fundraisers. The information that is missing in this recent announcement is that the Association of Fundraising Professionals has included this rule in their code of ethics originally adopted in 1964! Using commissioned fundraisers has been regarded as both sleazy and ineffective by non-profit managers for at least a decade. So it is shocking to hear large charities like Sick Kids and World Vision only swearing off the practice in 2007.

The next provision of the code mentioned in the October 22/07 article is that charities will adhere to a code of honesty in reporting to their donors. Imagine Canada is said to be cracking down on “wild claims of success by the charitable sector.” Good idea but very vaguely worded.

Nowhere in the report is there a clear criteria how “wild claims” will be detected nor how the sector will amend the practice. While some issues are more complex, there eally there are a number of ways that some charities deceive the public that could be identified, a test of accuracy applied and the practice cleared up fairly easily. One example is the use of self-aggrandizing and confusing titles for organizations and programs. Many organizations have “International”, “World” and “Canada” or “Canadian” in their titles. The public can be expected to presume that an organization with “International” or “World” in the title has directly-administered programs in a number of countries around the world. The sector should/could agree that having directly-administered programs in less than a set number of nations, (7, 5, … 3?) and using “International” or “World” in the charity’s name or program title, is deceptive. By the same token, charities that describe themselves as the X organization of Canada, lead the public to believe that they offer programs and services to Canadians in a number of provinces. Imagine Canada should include benchmarks for the use of these common attributions.

Another way that “wild claims” could be curtailed is by adopting a strictly enforced standard for reporting on statistics for programs. This is straightforward for programs that are solely and directly administered. It becomes more difficult in jointly-run programs. Sometimes charities give small donations to programs and then claim the entire program and its activities as part of the work of the charity. Real collaborations between agencies in the charitable sector is to be encouraged, but the public should be able to tell clearly who is responsible.

Here is an example of the way this numbers dodge can work in the charitable sector. Charity X raises money to run a cross-country literacy program that involves authors in doing readings in remote communities for the purpose of both literacy awareness and also to promote local literacy programs. Then charity X contacts grass-roots organizations and gets them to do all the work, undertake the lion’s share of the work and all the marketing expense in organizing the events. Perhaps a small “how to run your event” manual is written by Charity X from freely available material found on the internet, providing a token organizing effort. Another token support is given to the event in the form of subsidizing author airfare for example—transferring a small amount of funds raised to actual program costs. Meanwhile there is virtually no work or expense by charity X other than the transfer of that small portion of funds raised and yet Charity X takes credit for a national series of literacy awareness events, and furthermore enhance their reputation as a national organization while potentially running no real programs in Canada and keeping the lion’s share of money raised for their administrative and fundraising operations. A staff salary is paid to a “program coordinator” but that person’s daily work assignments relate to fundraising and general administration. A report to donors on the project includes the information that X people attended events in 15 locations across Canada and X dollars were expended on program costs, however the report on program costs includes the salary paid to someone for administration and a pro-rated portion of administrative costs such as photo-copies, office suppliers… even if none of these were used for program materials. About 80 % of funds raised is claimed as being used in “program costs” with a modest 20 % being accorded to administrative support of the program. However a hard forensic accounting look at the program might show that only 10% to 20% of the money donated to the program was transferred to direct program costs in the form of low hassle airfare subsidies to grassroots groups organizing their own events.

This is the complex face of garden-variety “wild claims” in the charitable sector. This type of practice is damaging to the climate of giving in Canada. It also hurts legitimate charitable organizations, and is poisoning the working climate in the non-profit sector-- both within “bad apple” organizations and within the good organizations who struggle to compete with the “bad apples” who misreport activities, results and proportion of money spent on administration and fundraising.

While Imagine Canada is to be commended on this first step of a self-governing code of ethics, it is a very, very small step. Much more work is needed and it is not clear that this can be accomplished by the sector itself. In my next article I will attempt to write about what I see as a sickness in the heart of some charities and non-profits and some thoughts on how to tackle those difficulties.

Tags: Management, Leadership, Arts Non-profit, Charities, Donors Ethics

Tuesday, January 02, 2007

New money for the Arts in Canada

Organizations waiting in line for their first Canada Council operating grant got excited that this might be their year to gain some secure operating funds instead of depending on the ups and downs of one-time project funding exclusively.

Not so.

In Canada Council's newsrelease of October 2006, the method for allocating the funds was not spelled out although it was suggested that one possible way of allocating funds would be through,"a special competition (in the case of arts organizations which currently receive operating funding) or through the Council’s regular programs for individual artists and activities aimed at increasing public access to the arts."

Nowhere in the public announcement carried in newspapers across the country, nor in Canada Council's press release was it made clear that in fact the Council was going to priorize giving money to its existing operating clients. Yet when the , guidelines were announced to apply for the new funding this was the language "Guidelines. Who is eligible? Organizations currently receiving annual or multi-year operating funds may apply.

And what if your organization is not receiving annual or multi-year funding? The answer, "No further action is required at this time".

While the Council suggests that additional money is being allocated to project grants to help non-operating clients, I could not find anywhere on the site how much money is being allocated to which programs.

Note that to become an operating client of the Canada Council, an arts organization must already be in receipt of funding from their provincial arts council. To become a provincial client, you must be supported by any municipal funding body for which you may be eligible. Canada Council operating clients are among the oldest and richest arts organizations in the country.

My organization, the Toronto Philharmonia, has been in existence for 35 years, 30 years as a community orchestra--called at that time the North York Symphony--and spending the last 5 years as a professional orchestra. During that time we've given an annual classic music series, provided educational programs to local schools and offered adult education opportunities in music appreciation. Hardly a newcomer to Canadian arts.

But we are not operating clients of Canada Council. We've been told that we stand a scant chance of being funded under the professional orchestras program simply because there is a lack of funds in the program and our location in the mega-city (although serving the former borough of North York)makes us a low priority for funding. While nationally, music organizations receive an average of 30% of their budget through government funding, our orchestra has to raise 90% of its funding through private funders and ticket sales. Yet we are ineligible to apply for a share of the new funding. Is this fair? Is this what you expected to happen when the new arts funding was announced?

Once again, it appears that the rich arts organizations will get richer while smaller arts organizations serving local communities get the short end of the stick. If you don't think this is fair, please feel free to comment here but also let your local MP know that you'd prefer that new arts funding be distributed to the poorest arts groups in the country, not the richest.

Tags: Canada Council, Arts Funding, Arts Policy