Monday, April 21, 2014

Friday, April 11, 2014

The Arts Consultant: planning for a useful consultancy

How do you plan a consulting project and provide oversight to the workplan to get the most out of a time-limited relationship? It will be as good or as bad as your organization makes it!

Develop a project that is relevant to the organizational needs:

- successful consulting projects are driven by and responsive to the organizational strategic plan

- successful consulting projects are responsive to organizational strengths and needs.

- successful consulting projects have a draft plan in place before potential consultants are approached

- successful consulting projects are rarely driven by "friend of the board" consulting opportunities, to address shortterm needs due to staffing/funding shortfalls, nor projects proposed by the consultants themselves

Choosing the consultant. Find someone with strong relevancy to your organization's needs.

- Talk to colleagues, funders, professional organizations

- Look at the past experience of the consultant for indications that they know your sector and how to work with organizations of your size, especially when sectoral knowledge is very key to the project.

- Be sure the skills and expertise of your consultant is a match for the specific focus of the project, e.g. "social media marketing" and not just "marketing" if they are charged with a social media marketing plan.

- Be sure that the consultant you are in conversation with is able to be as hands-on and present in the organization or as independent as your project needs them to be. Be frank with the consultant about what you need and don't need.

- Discuss the draft plan with the consultant as well as the opportunities, strengths and limitations of your organization. Be receptive to suggestions that enhance your plan but wary of someone who wants to make huge changes to the plan. They may not be a fit for what the organization needs.

Assure everyone involved in the project is clear about lines of authority, responsibilities and reporting.

- In successful consulting projects there is organizational oversight. Who directs the consultant's work? Who intervenes if a consultant's work is not being done, goes off-course or is being disruptive of operations?

- Is there a staff member(s) assigned to assist the consultant? If so are those staff members aware of how they will be expected to assist? This needs to be spelled out, "You will be required to occasionally assist X by research and assembling information. This is not to take precedence over your regular work, should not involve more than 1-3 hours work per week."

- In successful consulting projects, staff understand the scope of the project and how it integrates with their own work and what they might be asked to do to assist with the project

- Do staff know what information is permissible to share? Be thoughtful about privacy legislation and your own valuable contact lists.

- Do staff understand the likely outcomes of the project? "The information you give us on information flow and 'who does what' in your department will guide an HR reorganization that could change reporting structure and job descriptions". Understanding the importance of the project will elicit buy-in.

Why consulting projects fail?

- Irrelevant projects: A marketing plan for an organization without the staff or finances to support the plan. A "think outside of the box" innovational strategy that is not sustainable due to known factors.

- Choosing the wrong consultant: You picked someone with a knowledge of foundations and government funders to plan and pioneer an individuals and corporate donor campaign.

- Absentee or "in your hair" consultants: lack of clarity about workplan and style leads to a consultant that no one can connect with, ("I'm sorry but I am in Abu Dhabi for 6 months and I need to get my cellphone unlocked before I can call you back") or a consultant who is disruptive of daily work with a barrage of phone calls, emails and drop ins

- Lack of oversight: Consulting project takes on a life of its own due to lack of oversight. Results unlikely to reflect original goals and project either becomes irrelevant or disruptive. Results become hard to assess when it is unclear what the consultant actually did. Staff resent a consultant taking on roles that is in their job description.

- Lack of clarity about reporting structure/staff roles; Due to busyness and lack of information staff are uncooperative, stalling the project or the opposite, staff unduly priorize consulting project to the detriment of higher priority work. Consultant, unclear of how to get needed help, goes to anyone who answers the phone for help sometimes causing duplication and confusion. Consultant unclear of boundaries, contacts staff at home, via personal email etc. Staff who have no mechanism to refuse to put in extra hours for consultancy project ask for huge overtime payments or time in lieu due to work heaped on them by the consultant.

- Lack of clarity/process and ethical considerations in information sharing. Wary staff refuse to share information needed for the consultancy. Staff fail to priorize information sharing because they don't know how it will be used. Staff who misunderstand Consultant's scope share privileged information. Consultant offers the organization contact information that is not supposed to be shared. Our contact list is shared against our wishes and our contacts complain. Individuals added to our contact list complain about spam. We see a decline in funding results from known sources the following year and discover our list of funding contacts is being used by a competitor who has hired our former consultant.

Key Points:

- Strategic needs and long-term goals should drive the project, not shortterm opportunities or needs

- Select a consultant who matches the project, the organization and the work style of the team

- Provide clear oversight to the consultant and clear responsibilities/communication lines for the staff

- Get the necessary buy in from staff by sharing the project's goals and likely outcomes

- Be thoughtful about information sharing making sure protections and permissions are clear

- Track the project regularly assuring reports are accurate

Friday, April 04, 2014

"Ends Justify the Means" Dilemmas in the Not-for-Profit Workplace

In the not-for-profit and arts world I believe we set ourselves up to be uniquely vulnerable to the pitfalls of ethical systems based on utilitarianism. This is the ethical system in which the "good of the many" always outweighs the "good of the few", a system that becomes challenged when the means are not ethical in and of themselves. In not-for-profit workplaces we think about "Ends" all the time. Right on the top of all our literature and websites we spell out the "Mission". We are focused and passionate about the mission of our organizations, whether it is feeding the hungry, housing the homeless or assuring the survival of a classical orchestra.

Into all this passion and energy for achieving worthy goals comes a number of roadblocks that can make us, as non-profit staff and managers, feel that government funders, sponsors, regulatory bodies, are treating us unfairly, stacking the deck against the success of our organization to achieve our mission. Those challenges include: the preference for funding projects and program costs, over needed support for core operations; shifting priorities and programs from governments and foundation funders; narrow program objectives that don't match the needs of the communities we serve. And some days we feel like if we hear the word "innovation" one more time, we'll scream. We twist our programs pretzel shaped to try to qualify for those innovation grants when, really, we think that the way we have always done things is probably pretty soundly based on best practices.

Between the passion to do good and the frustration about roadblocks that seem illogical, unpredictable and insurmountable there sneaks in a philosophy of the "end justifies the means". Whether we bend the truth a little bit in our funding application to make our planned activity seem like a better fit, or we move expenses in accounting lines to shift expense from administration to program and marketing, we are embarked on a slippery slope. Tensions mount in organizations when doing whatever it takes to get or keep funding pushes staff members beyond their comfort levels.

These are not victimless crimes. Public dollars, the reputations and health of workers, the continuation of programs and services that the public counts on are jeopardized when organizations foster a culture of unethical expediency. Staff members feel helpless in organizations where they are not just asked but required to do unethical things: back-date mail machines to send in applications after funding deadlines, forge a signature because someone is unavailable, spend all their time working on one project that they are not funded to work on and neglect the work they are funded to do (a common way of shifting funds from one program to the other surreptitiously), directly shift funds from one program to another without the funder's knowledge, invent statistics, report fundraising costs of a special event fundraiser as a "program" cost, report expenses of one project as the expenses of another, double and triple raise project revenues for one pet project while reporting a reasonable budget in each request, over-spending ridiculously on one area. . . all things that have been sanctioned in organizations I have worked for in the past. Yet there is little over-sight of non-profits and whistle-blowers at the staff level often have their careers ruined while they sometimes see the non-profit manager who forced the questionable or outright disgraceful practices be backed up by non-profit boards and even to be recognized with national awards.

Any solutions have to deal with both the problem and its causes. Adequate funding of basic operations of non-profits that are operating effectively in the public good will stop the need to fudge program costs to cover operations. I could say that Boards should stop propping up corrupt leaders but . . . that's not going to happen. The "friends of X" board is alive and well everywhere. I have come to the conclusion that there needs to be tougher regulatory bodies at the provincial and federal level that will investigate allegations of mismanagement of publicly funded non-profits. Working currently in a very well-managed and ethical non-profit has given me new perspective on the harm that unethical non-profits do to workers, funders and programs.

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Founders' Syndrome: Why we should all be concerned

What is founder's syndrome and why does it affect so many smaller arts and non-profit organizations?

The strong entrepreneurial personality that developed a new organization may be unskilled at or unwilling to delegate. The tireless worker that was willing to pull all-nighters to get in last-minute grant applications may be unable to schedule work or effectively manage their time. The genius that came up with spontaneous project ideas may not be willing to work on long-range plans or within budget guidelines. All of the affects of founder's syndrome results in limiting the growth and effectiveness of organizations and often creates toxic environments for workers, artists, clients.

How does Founder's Syndrome develop in organizations?

Founders alone cannot create an organization with Founder's Syndrome. It takes a step-by-step, person by person tacit agreement to cede power to the Founder by Board Members who should be providing governance to the organization. It also requires funders, volunteers, staff, colleagues and other stakeholders to decide to continue to support the sick organization or to leave silently. Over the years it there may be numerous loud and clear signals that there is something terribly wrong in the organization but no effective action is taken to address the problem or to provide help to the Founder to assist them in developing a more effective leadership style before they stifle or bring ruin to the organization they founded.

What are the symptoms of founder's syndrome?

What are the options for an organization with Founder's Syndrome?

1. If the Founder recognizes the problem, get them help through professional leadership counselling.

2. If the Founder does not recognize the problem you'll need buy-in from more than one organizational level to effect change. Without support from Board, Staff, and Funders you will not be likely to succeed. Staff driven efforts alone result in Board backed firings that can ruin careers and even the health of staff members summarily dismissed for the efforts to alert the Board to the dysfunction. Board-driven change processes that lackstaff and funder buy-in can result in funding cuts, and/or sabotage at the staff level and ultimately Board fatigue, resignations, replacements. Funder led calls for reform without organizational support can result in financial hits for the organization but no real change. The organization will find new funding partners or fail, but will be unlikely to effect real change to suit a funder unless there is recognition of a problem.

What are the implications for staff employed in an organization with Founder's Syndrome?

1. Recognize that you are in a very challenging environment and you may not be able to effect change. Go easy on yourself.

2. Consider your options and prepare your exit strategy even before it's necessary.

3. It is unwise to try to effect change in the organization unless there is a Board initiated effort for organizational change.

4. If you elect to stay in the organization focus on small goals or achievements within your area of responsibility with minimal opportunities for friction with the Founder.

5. If you choose to whistle-blow, be prepared for a very difficult time and possibly lasting career damage. It might be personally advantageous to simply resign.

6. Work within the non-profit sector to promote awareness of this problem and protections for workers.

Tuesday, July 03, 2012

Delegation # 1: Why managers are afraid of delegating.

When you talk to unhappy employees and ask them what is wrong with their jobs or their relationship with managers, the leading issue is usually poor delegation techniques. In the arts and non-profits we are often working as managers having no business training in supervisory management and as employees we are working with bosses who may be wonderful in their fields but don't know the first thing about managing people.

Why do so many managers fear and avoid delegation?

# 1. Fear of loss of control.The inexperienced and insecure manager is afraid that if they don't do everything themselves things will spin out of control and they will lose authority to shape projects. Let's examine this fear:

- If you recognize this as your own fear as a manager, remember that you have the power to require employees to check in with you, report progress, and you can set the schedule for completion of stages in a project to build in time for edits and tweaks you feel are needed.

- Delegate from a sense of your own power and your fears will fade

# 2. Fear/Dislike of employees stealing credit or sharing the limelight.

Let's look hard at this fear:- Just as your organizations failures ultimately reflect on you as a manager, so do the successes

- A part of maturing as a manager and human being is learning to enjoy your new role as a mentor to a new crop of professionals. Their successes are your successes.

- If an employee truly tries to steal credit or becomes unduly competitive, that is a separate issue that you can deal with, ultimately you have the power to fire them so why be bothered by small expressions of ego?

#3. Don't feel you have time to teach employees how to do the delegated work or supervise them:

- If you are feeling time crunched, only effective delegation will get work off your desk so a small hump of extra work will pay off in the long run

- Part of delegating the task can be assigning the employee to job-shadow, read, take a course, do online tutorials to acquire skills. You don' t have to take on all the training yourself.

- While a lot of supervision might be needed the first time an employee takes on a job, it will decrease markedly the next time.

- Delegation and supervision IS your job as a manager. Likely all the work on your desk is really not your job and needs to be delegated.

#4 Worry that your employees will make mistakes, use methods you don't approve of, generally goof up something.

- Employees will make mistakes and that is a part of learning.

- Planning for training and supervision and scheduling to allow for error correction is part of your job as a manager and part of your effective delegation strategy.

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Writing Grant Proposals as a Team

Grantwriting in a Team Environment

Grants written with a collaborative team are usually stronger, more realistic and tied to the real activities and history of the organization and provide opportunities for team-building. Grants written with a collaborative team can also be among the most frustrating and time-wasting of activities if there is no plan for the collaboration and team members don’t adequately understand their roles.

Why write a grant collaboratively?- Capitalize on multiple talents

- Get multiple viewpoints

- Increase organizational and/or partnership buy in to the project proposal

- Define roles

- Choose the team

- Chart a realistic timeline

- Choose tools

TEAM ROLES:

NOTE: Many times one individual is responsible for more than one role in grantwriting, but it is useful to break down the roles to understand all areas of responsibility. For most grants the roles include:

1. The Grant Lead: This is the person, often referred to as “the grant developer” who is delegated responsibility for team leadership on the grant. They define the process, assign grant tasks, manage the timeline and are ultimately responsible for declaring when grant components are final. They may or may not be the actual grant-writer.

2. Grant Researcher: This role requires someone with skills and experience in researching funding bodies and (if applicable) expertise with the fundraising database used by your organization. They identify funding programs with high relevance to the activities of the organization.

3. The Grant Analyst: This role requires someone able to summarize the grant requirements and provide the information to key individuals within the organization for decision-making about whether and how to proceed and to set out key requirements needed to be met (such as signed contracts).

4. The Organizational Historian/Fact-checker: This role provides up to date content on organizational history, mission, projects, as well as needed documents such as board lists, audited financial statements, incorporation papers, photos, biographies/profiles of team members and partner organizations.

5. The Needs Manager/Project Rationale Researcher: This role is able to research the “need” that the project addresses whether it is a need in the community or an organizational need. Articulating the need is important to making a case for the relevance of your project (whether the application asks you to answer questions about needs or not).

6. The Grant Writer: This is the individual who takes all content provided and crafts it into a coherent argument that is presented with one voice through the document. They are ultimately responsible for style, grammar, format.

7. The Collaboration Organizer: This role is responsible for the nitty-gritty of the collaborative effort, sending invitations to team members, organizing meetings according to time-line, chasing people for content, and tracking the receipt of all needed materials, signatures, support letters, etc.

THE GRANTWRITING TEAM:

While above, I have defined the ROLES needed within a grant-writing process, one team member will likely assume more than one of the roles. Your grantwriting team may be 2 people or 20 people (or more). Most grants involve 2-4 key contributors with some input from stakeholders. Who you choose for your team depends on your organization and the nature of the application. While you typically would want only one person assigned to some roles (such as project leader and/or lead writer), others can be performed by teams (such as researching community needs or literature surveys, getting equipment quotes).

KEY SKILLS:

The skills you need to assure are on your team include:

1. A professional within the organization who has key insight in the organization’s history, goals, and able to speak to the nature and importance of the key points of the proposal.

2. A grantwriting professional who is skilled in researching funding opportunities in tune with organizational needs

3. A budget specialist able to craft a realistic project budget and answer financial questions about organizational finances

4. Writer/editor who will be the “voice” of the grant--responsible for the tone, grammar and persuasive language of the grant

Unless one person has ALL of the skills above, you need to develop a team however small! If you are the Grant Lead--taking into account both the roles needed in the grant and the list of key skills--consider who will make up your team. Following the rules for good delegation, you will need to assure that team members understand their role(s) on the team as well as the role of others. Each team member must have the tools and resources needed to perform the tasks (time, materials, budget) and the authority (existing or clearly delegated) to successfully fulfill their role.

TIMELINE:

Chart your timelines with key points for completion of stages of grant development through a work back schedule from the due date with full understanding of that due date which can vary from “postmarked by X date” to “must be in our hands by 5 pm on the due date”. While generally the earlier the better, a too early start date can undermine any sense of urgency about the work and lead to procrastination and dropped balls. Likewise some RFP have tight timelines that mean that intensive work will be unavoidable.

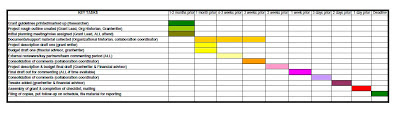

Generally the charting done by an experienced Grant Lead will look like this:

By making your first draft completion date far enough in advance, you can allow for a second round of commenting and revision if necessary or if the project gets behind schedule due to external factors or difficulties in obtaining all information needed, you can forgo this step.

TOOLS FOR COLLABORATION:

Do you need special tools for collaboration? Not necessarily. It depends on your team, process and proximity. If a grant is being written by one person who edits submitted content and incorporates 2-3 team members content and comments (the majority of grant-writing scenarios) no special tools are needed. Emails, word documents or notes written on a table napkin, will all be incorporated by one individual into a master document that is not available for editing by anyone else. No tools beyond a word processor needed.

Where it gets dicey is where multiple individuals are working on writing/editing sections of the grant collaboratively (and there has to be a strong rationale for this approach). Here version management becomes difficult and if there is no system in place, valuable content can be erased by a contributor who lacks the big picture. The grantwriter has started by organizing content into paragraphs dedicated to single ideas, ensuring that all building blocks are in place over the entirety of the grant. This can become lost as new writers add irrelevant details to paragraphs unaware those ideas are stated later, or in a different section of the application that they may not have in front of them. Simply tracking the revisions becomes a chore. Take this as an example: Susan has written the first draft of a project timeline that outlines a series of workshops. She sends it out simultaneously to Sandra and Kevin by email. Sandra gets back to Susan first with her revision and has added 2 workshops to the list. Kevin (working on the original document) adds one workshop. If Susan saves the most recent edit (Kevin’s) as final, she will not have incorporated Sandra’s input. So how will this be avoided without adding hours of pouring over revisions with a fine tooth-comb?

The need for a unified voice and coherence within the full application dictates that:

- The process for editing needs to be clearly articulated

- There needs to be a start and end point to edits (a date where no more edits will be received and the key writer will consolidate).

- A system or tool for tracking versions must be decided on and used by all contributers

- The final edit must be done by one person assuring a single voice and coherent thread.

MS Word “Track Changes”:

When two or three editors work on a document and only one or two revisions are anticipated, the tools within Word for tracking changes, emailed back and forth will likely be sufficient to the team’s needs, provided they agree on version labeling and documents are not sent to multiple editors at one time without the knowledge of the key writer. The key writer needs to know which version of the document the edit is based on to not lose content previously submitted.

The drawback of “track changes” with multiple edits and editors is that the document becomes unreadable unless the revisions are hidden by selecting “show final”, however in that view content crossed out by one editor which may be necessary and need to be restored can be lost.

Google Docs

Google docs are similar to MS Word’s track changes in look and feel. The advantage of using Google docs is that two people cannot work on the document at the same time so that the most recently saved document is always based upon the work of all previous contributors.

Wikis

Wikis were developed specifically for collaborative writing and allow team-members to look at all version histories. Within a wiki, it is easy to roll back to a prior version or ensure content is not lost. There are a number of free wiki spaces available online and using wiki tools are highly recommended where team-writing for sections of a grant involve three or more people and or is anticipated to involve more than two rounds of editing. My favorite wiki spaces include: http://www.wikispaces.com/ and http://pbworks.com/

Proximity (a collaborative tool we sometimes forget):

Grant-writing teams seldom go off the rails when collaborators work in the same office space and work the same days/shifts. When they do not, it is important to be able to simulate the good synergy effects of proximity. Wiki tools help with this. Meetings, web conferencing, shared Skype calls, and even meeting virtually in online environments can avoid the pitfalls that occur when collaborators feel they are working in a vacuum at some points and are surprised by input from other team members at other points.

Symptoms of failed collaborative grantwriting:

Reluctance to contribute in a timely fashion: One of the leading signs of a process that is failing is the hording of information and avoidance of content sharing until the last moment of a grant deadline. People do this as a defense when they feel that earlier input will be lost or be subject to so many revisions that it will add to the time they will actually be required to spend on grant-writing. "Why contribute now, it will only have to re-done 10 times?"

Lost or confused content: Editors are simultaneously working on the same document making tracking versions difficult to impossible. "I'm sure we had something in here about X in an earlier version. Where did it go?" The wrong tools are being used for collaborative writing.

Surprises and conflicts: "Why are you working on X? I've already done it!" The team and roles were not clearly defined.

Loss of engagement by project and/or writing lead: You send your lead writer comments and edits galore and they stop responding. There's likely a timeline problem. The editing process needs to have a clear end-point so that final draft can be constructed. Grantwriters who are unsure of when they are needed for final edits may be reluctant to contribute until they are sure the dust has settled to avoid wasting their time.

Lack of consistent voice and format in final grant: Editing and commenting has not been terminated with enough time for grantwriter to polish and format or grantwriter has not been correctly delegated authority to override edits that are off message.

Lastly take this quiz

- We always have organizational buy-in for our grant-writing before we begin. Yes/No

- Our grant team all know their own roles and responsibilities. Yes/No

- All team members know from the outset who will contributing and how. Yes/No

- Our grant process has a defined time-line for key steps. Yes/No

- Our tools match the number of collaborators we are involving. Yes/No

- We work in close proximity or have plans for meeting/conferencing as needed. Yes/No

- We have no difficulty tracking revisions to grants. Yes/No

- We are never surprised at the last minute by missing documentation or signatures. Yes/No

- Team members contribute on schedule with confidence their input will not be lost. Yes/No

- Grant proposals have a unified voice and a coherent argument on completion. Yes/No

SCORING:

Give yourself a point for all your “yes” answers.

A perfect 10: Where do I apply to work for you as a grant-writer? Great going.

7 to 9: You are like most organizations, doing most things correctly but there’s probably just one area where you could avoid conflict and time wasting if you planned a little better.

4 to 6: You are probably experiencing some staff stress or even conflict. You may be wasting time and energy due to duplication of work by people not understanding their roles and/or doing intensive last-minute grant-writing due to lack of pacing.

Less than 4: Grant-writing collaboratively is either very new to your organization or has become a huge trial that your staff members view with dread. They react with either avoidance/delay strategies or by jockeying for position when a grant-writing task is announced. The process is likely always contentious and the results are worse than if one person completes the grant leading you to feel it is better you do it yourself. (Most of us have been there.) Consider, if you feel this way, whether your team really lacks the skills or whether the process is at fault.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Commonsense Social Media for Small Arts Orgs

Do remember to include in your plan all your skills that are relevant to a successful social media campaign

You've been talking to your supporters, colleagues and audience for a long time and you know them and their interests better than anyone. You also are skilled at reaching out to them creatively and inexpensively. For pete's sake, you are artists! Those skills will be key in making your social media campaign a success!

Don't be phony in your social media voice

Social media is ... well... social. It's got a tone like talking to your neighbours about your work today. Your neighbours and friends will be delighted to hear your voice saying "here's what we've been working at in the studio today" in your own voice. Having that voice delegated to someone outside your company will feel phony and insulting to them. If it feels like a trick in social media, people turn off.

Do have the confidence to run your own social media campaign

The best social media campaign is grass-roots, just like you started your arts organization.

Don't feel you have to spend big bucks on a social marketing professional

No social media "guru" knows your art and your audience like you and your staff do. So what if they have 2,000 Twitter followers, are they relevant to you, or just other social media gurus all jabbering to each other with re-cycled tweets and links?

Do take the time to blog yourself

I know you don't have the time, but you know the best blog-posts are short ones. Here's some good tricks. A photo is worth 1,000 words. Snap photos with your cellphone or digital camera and post to your blog with a small comment. Tumblr is a great platform for quickie bloggers. If you are more of a talker than a writer, make brief voice recordings and ask someone to transpose them as blog posts. Or, make a time to sit down once a week with someone in your organization who does like to write and give him or her a list of things to interview you on. Or just have a chat and record it. A 30-60 minute meeting about what's going on with the company right now should yield a week's worth of blog posts that can be timed for daily release.

Don't let a staff member turn the Artistic Director into a sock puppet

If a post is listed as being from the Music Director or AD, it really should be that person's words. To charge a staff person to write on your behalf without input or approval isn't fair to them or you.

Do make meaningful connections with colleagues and organizations with common-cause.

Guest write for your colleague's blog and share your posts with organizations that will be interested for example your post on set-construction with an umbrella theatre organization or your post on financial planning with an arts administration website. Ask your colleagues to post to your sites. Include the news from other organizations in your tweets and Facebook updates.

Don't be territorial in social media

If all you tout in your blog, facebook page or twitter stream is your own news, you will be preaching to the choir instead of reaching new audiences.

Do listen to your followers and engage with them

Social media is social, so a part of every social media campaign should be to spend a little time reading what your followers are saying: about you, about other arts organizations, and about things in general. Comment, re-tweet, and thank them for their favorable mentions of your organization.

Don't be a broken record

You wouldn't invite your neighbour to a party and then invite them again, and again, and again, using the same message, would you? So invite and follow-up in social media much as you would in other media.

Do use more than one social media that is relevant to your company

As a suggestion, pick one blog platform to share your news in greater length than a twitter post or Facebook update allows. Create a Facebook group for your followers to publicize events. Use a photo site like Flickr or Picasa to host photos & slideshows and a video site like YouTube for video snippets. You may or may not find the social aspect of the photo & video sites useful. But embedding photos in blogs and Facebook posts enlivens them. Finally use Twitter to connect followers in short news bursts to your content in blogs and Facebook. As you develop your social media campaign you will find other tools to use, but no one tool will make effective use of your social media time or effectively distribute your news.

Don't get too enthusiastic about linking and automating your social media messages

As we've seen different social media platforms have different uses and formats. A 140 character twitter post sounds brief and possibly rude when repeated on Facebook, so be thoughtful about linking media. Auto welcoming followers used to be recommended but has become so prevalent that many people regard this as spam and will unfollow anyone who uses the tools. Services that spam followers with auto quotes are fairly universally despised and will lose you followers.

Do use buffer apps to time distribute your posts.

You may want to do all your social media posts at one time of day and all your blog posts one day a week, but many posts at one time will bore your audience and also not reach some potential followers. Twitter streams are one place where people only are likely to see the posts made in the last hour, so use a buffer to send your tweets over the day (twitter is probably the only social media where you can repeat a key message like an event reminder). Facebook posts can also be spaced through the day. (I use http://bufferapp.com ) and you can choose whether blog posts will be published now or at a future date.

Do remember that the message of your company is important

Probably only the artistic director and/or senior management can really articulate key messages about projects, mission and artistic direction of the company. Identify the person or people within your company who will craft the social media messages. Make sure everyone is comfortable with the plan and will follow-through.

Don't give the social media job to the intern

The intern may be able to Facebook up a storm about their keg stand at the party last night but that doesn't mean they know how to tell your story to your key audience. Interns can help but don't leave them in charge of the process or be prepared to accept the results.

Do use your grassroots skills in building up your number of followers

Hey you built your mailing list & email list from 0 to thousands, right? How? By asking people who visited your website to join the mailing list right? By capturing Box Office data, by asking people to enter contests and by asking people to save money, save the trees by signing onto your email list instead. When you have events, that's the time to ask people to join your Facebook group or follow you on twitter. Make it easy with slips of paper they can take away, inserted in programs or available in the lobby on info tables.

Don't get greedy

Don't try to build followers by following hundreds of random individuals. They won't stay and aren't relevant to your success. In the worst case scenario you could lose your account through being listed as a spammer. Having 100 followers who actually come to your events is better than having 3000 followers with only 25 actually coming to your events.

Do give incentives

You know how to do this! Give potential social media contacts incentives by running contests for free tickets or other goodies available only to Twitter followers or Facebook Friends (but don't make these goodies valuable enough to annoy other contacts).

Do evaluate your social media plan

How are you doing? Did you sell out a show using just Facebook? Are you getting more re-tweets of your news? How many lists is your twitter stream on? How many mentions did you get on Twitter last month? How many blog visitors have you logged (Google analytics or site-tracker have good tools).

Don't get discouraged if you don't see results right away

A good social media campaign is not going to happen over-night for most of us. It is slogging work like building a mailing list. If you are not seeing results after a few months you may need to fine-tune your plan, discover why your blog posts and updates are not engaging & growing your audience.

Do remember the goal

You want to deepen the engagement of your existing audience with your company so that they will be more likely to support you by increased attendance and financial contribution. Plus, you want to reach new audiences-- while spending less money on advertising and postage. You also want to be able to brag about how efficient and green your company is in achieving these goals.

That's pretty hot stuff so it's worth some work, right?

Friday, February 11, 2011

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

US survey shows grantmaking fell 8.4% in 2009

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Arts Presentation Contracts

1. Self-present

2. Contract of Services

3. Co-present

Most difficulties that occur, happen when the type of contract is misunderstood or all aspects of the arrangement are not defined and signed off on by both parties.

Self-presentation:

If my arts organization is "self-presenting", we are responsible for the artistic content, all the costs, raising the money for the project, marketing, and all the ticket revenues are ours. We may be presenting in a venue we own or we might be renting a venue. In a rental venue we might be subject to some house rules and we might have access to some inhouse marketing vehicles (a lobby lightbox or an e-newsletter). We need to sign a contract for the rental agreement but at no time should our self-presented concert be represented by the venue as a part of their series. If they wish to change the nature of the relationship to a co-presentation agreement, you should be looking for concessions on rent, etc.

Contract of services:

Your organization, company, church, or event is hiring the services of my arts organization. For example your church wishes my orchestra for an Easter concert. You can request specific repertoire if you are willing to pay the costs of the orchestra learning new repertoire or save money by taking our suggestions. You set the time of the concert, are responsible for all ticket sales, all revenue is yours if the event is ticketed. The orchestra is paid a flat fee that we have determined will cover our costs for the event. We will have to assure in our contract that we don't incur extra costs. The things we will need to assure in the contract are: the repertoire, start and finish times for the concert, where the orchestra can warm up and securely leave their belongings during the performance, when the orchestra can take the stage, meal arrangements for the orchestra (if applicable) and orchestra name/logo recognition on advertising and materials.

Co-presentation:

My orchestra and your choir decides to co-present an Easter concert . We will have to determine:

1. Who determines the repertoire and who pays for the rental sheet music?

2. Who pays for the hall?

3. Who is going to pay for and supervise the marketing campaign and what sign-off will be needed by the other organization?

4. How will ticket sales be divided? What about series subscribers? Are their seats included? Where will they sit?

5. How are we each going to make money? Split the sales 50/50 or some other arrangement that is equitable balanced against the cost sharing arrangement?

6. Who is responsible for rehearsal costs?

7. What spaces will each organization use in the hall and for what periods of time?

Is it really necessary to spell these things out in a contract? In my experience it is, especially in the complex arrangements of Co-presentation agreements. I have seen the following problems occur in co-presentations that were uncontracted or with a very vaguely worded agreement:

1. Misunderstandings about the amount of tickets available for sale by each organization.

2. Unhappy subscribers who thought the concert was included in their subscription but no seats for them had been negotiated.

3. One partner representing the concert as though it was theirs alone. (no agreement on sign off on marketing)

4. One partner holding up marketing with lengthy tweaks and changes, jeopardizing sales. (no time-lines for approval of marketing).

5. Last minute demands for one organization to pay the rehearsal costs of the other organization. (not clear that each was responsible for their own costs).

6. One organization changing the repertoire and/or time of concert without consultation, confusing artists, public, and rendering promotional campaign invalid. (repertoire and time of concert was not spelled out in contract, nor that such would be by mutual agreement only)

7. And frequent disputes about smaller issues: sheet music rental costs, lobby sales, sponsor signage.

While it is hard to think of everything, I hope this gets any new arts manager asking the right questions about presentation contracts. If you spell out all the obvious issues and finish with a clause that suggests how any new issues will be handled, "at the discretion of X" or "by mutual agreement" you should minimize conflict.

The worst situations have occurred when the parties totally fail to understand the nature of the contract. I once inherited a rather vague co-presentation agreement with a choir. Not too far into the process of planning the concert I discovered that the choir thought the contract was a "contract of services"in relation to what money they expected from us (all their rehearsal costs and music costs covered) and was a "self-present" in terms of their marketing and ticket sales. They had put the concert on their subscription season (exhausting most of their share of the tickets with no additional revenue for them) and had gone on to sell more tickets, double-dipping their ticket share and cutting into our potential revenues. Basically they wanted it both ways, and that's not how the world works.

If the fundamental nature of the agreement is clear, and the large issues are settled, it is not hard to negotiate solutions to smaller issues as they arise.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Would your arts "entry" job be a fit for those looking for an arts "exit" job?

If an organization needs experienced grantwriting, financial management/budgeting, and arts marketing savey, they are unlikely to find that in an entry level staff person. It takes a few years of working in an effective team setting to learn these highly specialized skills. A great fit for such an organization may be an arts worker at the other end of the spectrum, easing into retirement or exiting full time arts administration in order to work on their own artistic or entrepreneurial projects.

Friday, December 18, 2009

The Value of Sharing: Social Engagement

No one is better placed to answer these questions than the people behind the "Share This" applet, that is most used to link social networking applications (for example post a link from a blog post to Twitter). Their articles and charts are invaluable in deciding which applications you should be focusing on in disseminating your message.

The Value of Sharing: Social Engagement

Posted using ShareThis

Friday, July 03, 2009

Michael Kaiser's "The Art of the Turnaround"

Kaiser says that the quality of art matters, be bold, be brave be revolutionary. Know your Mission and stay on Mission, and spend the money it takes to do it right and market it correctly. You cannot save your way to financial health. He says that the arts are remarkably efficiently run and do not have a spending problem, the arts instead have a revenue problem. Nor can arts organizations win by compromising the art by trying to vie with popular entertainment biz by watering down their season with pop and shlock. Any pickup at the box office will be equalled by loss of donations and funder support.

It makes me tired --as it did Jodi-- to hear this touted as new advice. The question in my mind is, "why does arts management common-sense so often fail to be implemented?" And the answer, I believe, is that there is a flaw in a structure which gives governance of our cultural assets to mostly untrained groups of volunteers, with little or no oversight or accountability. I have seen Boards do amazing things from time to time--saving and revitalizing arts organizations. But too often competent arts managers stagger and fail under the weight of dysfunctional boards that-- while perhaps composed of well-educated and competent individuals-- cannot seem as a group to acquire the knowledge or retain the organizational memory to plan well for their organization's success, or to carry good plans forward into future years of implementation.

If public funds were invested in building a bridge, and the bridge collapsed, people would ask questions, folks would be held accountable, fault would be found and those at fault would pay real costs. I wonder why we are prepared to invest dollars in arts organizations (and non-profits in general) and yet feel we don't have the right to hold Boards accountable?

Wednesday, July 01, 2009

Canadian Corporations vow to continue charitable support

Many companies suggested that their multi-year commitments meant that they had an inability to do much to respond to new requests for funding. At the same time companies report many more new requests coming across their desks as charities feel the pinch.

Austere times have meant a shift in priorities for corporations. Galas are going to find it more difficult to sell corporate tables as company heads find it difficult to justify thousands for black tie dinners when they are laying off staff and the charitable needs of healthcare, housing and poverty relief are in the news daily. Many charities are responding with changing their fundraising events or radically scaling them back.

Arts, culture and sports will be the losers as corporations continue to migrate funding to education, healthcare, and community programs.

Accountability is a key word in corporate funding these days. Corporations are selecting priority areas for their charitable dollars and now more than ever, projects seeking funding need to demonstrate how their activities are a fit with corporate goals. Reporting back to the funders on the reach of their corporate dollars--while always an important step in fundraising--is not an absolute requirement for ever being funded again by the corporation.

The 7 tips for non-profits in tough times is well worth reading this small quarterly.

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Grantwriting Basics -- Grantwriting 101

Since the bulk of my grantwriting has been in the Canadian arts--where I have to assume a type of applicant and type of funder--that will be the basis of my examples.

Corporate fundraising uses some of these same techniques but as it is substantially a different process than grantwriting, it will not be explicitly covered in this article. Corporate foundations, on the other hand are foundations and should be handled as a part of your foundation campaign.

IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL FUNDERS

Know your government funders and programs: If you are an arts or non-profit management professional, you likely already know the major funders for your program activities. In the arts at the national level you will be researching programs primarily from Canada Council and Heritage Canada. (From time to time other departments offer programs for foreign travel, international marketing of arts events.) Provincially, you will be looking at provincial arts councils and tourism programs that are available to support marketing for cultural events. Municipally or regionally, you will be looking at the programs of civic, regional, or county arts councils and regional/local tourism initiatives. Don't be afraid to call the Officers administering the programs to ask what programs fit your activities. Book a meeting with them if you are a new grantwriter, or new to the discipline, organization or geographic area. You may learn about programs that fit your planned activities that you didn't spot on the website, or in the literature. Establishing a good relationship with your Grants Officer is a really important first step in grantwriting for an organization.

Subscription databases: If you can afford them and you don't have a good list of funder contacts in your organizational records, you may want to subscribe to one of the subscription databases that are out there. They are expensive but it will only take one additional foundation grant that you would not have received to pay for the Bigonline database or Foundation Search Canada . Even one year of a subscription database will help you build your list of funders to the point where you may not need this resource in future years if cost is an issue. Note that these resources are not without some errors. I have found that where my organization has had an active relationship with a foundation, I have often had more accurate information regarding contacts, programs or even contact information changes. Building and maintaining your own contact list geared to your own program relationships/fits is irreplaceable.

Public tax information of charitable foundations: Okay, you can't afford an online database but you don't have much of a list of past donors in your organization. In fact the most recent foundation files are dated 1999? Sigh. I have so been there and done that. My commisserations!

Here is a real tip. Foundations are in themselves charities. As such they have to file a charitable information return with Canada Revenue. And that return is available to you free ONLINE. You can search the name of any foundation you are interested in, or search on a search term like "Foundation", or by city, to net yourself a list to browse through. You can open up the information to see who is on the Foundation's board and which organizations they have given to in the year of the return.

See below a screen shot of a search on all private foundations in Ontario sorted by city. All those with icons of returns on the right have accessible returns.

Buried deep within the return you will find a list of the projects and organizations funded by the foundation and the amount of each grant. This, together with the listed mission of the foundation, will give you a strong indication about whether this foundation is a fit for your programs and also what level your ask should be at for a program such as yours.

Buried deep within the return you will find a list of the projects and organizations funded by the foundation and the amount of each grant. This, together with the listed mission of the foundation, will give you a strong indication about whether this foundation is a fit for your programs and also what level your ask should be at for a program such as yours.

Finally access the foundation contact information of those foundations who fit and add that contact and any other information about website, deadlines, application forms and process to your grantwriting calendar.

Search public and foundation funders of projects like yours: You know who your competition is, who your colleagues are in the community and in neighbouring communities, and a little skill with online search engines and you are able to come up with some unique search terms that will generate a list of programs and services like your own. When you see a pattern of funding projects like your own, pull out all the stops to track that foundation or charitable giving program down. These are key funders with high probability of success.

Don't forget local family foundations: Sometimes we overlook family foundations in our neighbourhoods who may not have a discernible pattern of giving to projects like our own. That is because their giving is focused on all quality of life projects IN OUR BACKYARD. They give a little bit to fitness, some to amateur sport and some to education. If we are looking for "arts funding", we may never find them. However as the local symphony or community arts organization in their community of interest, we fit solidly within the mandate of their foundation and they want to support us! Don't deny them the chance to give us their money.

PREPARING ORGANIZATIONAL AND PROJECT PROFILES: Annually when your next season is well advanced in planning and before the first major operational grants are due, it is a good practice to update Organizational and Project profiles. This main document will be used in the following ways:

- As is for press-release backgrounders, potential board members, foundation appeals to foundations that lack a set process, as backgrounders to foundation appeals with more targeted content in the main application.

- Tweaked for foundation appeals where the emphasis is on an aspect of the program, expanding some sections, condensing or omitting irrelevant content

- As fodder to cut and paste into relevant sections of government grant applications and into the application forms for those increasing numbers of foundations that have a formal application process.

- Mission, Incorporation date and charitable number--if you have a briefer version of your Mission, you may want to use it here.

- Brief history of the organization (updated, brief, and engaging)--focus on accomplishments, programs, community impact, staying away from tedious details that are of internal archival interest only. Quotes are great!

- Artistic or Leadership statement--Put a photo of your conductor or theatre artistic director beside their own words on what is exciting and valuable about your upcoming program. Don't under-estimate the ability of Artistic Leaders to frame the importance of their work. If they won't write something for you, give them a phone call, write down what they said and send it to them for approval. It will help you as a grantwriter. You may be looking at a season that looks like a hodge-podge. You have no "hook" to hang your thoughts on, but when the Artistic Director tells you the season is a "dialogue between the conventional and the new, the audience's taste and the pressure for artistic innovation"... wow... you are off and running with and angle for your prose.

- Main Program Description--Describe your artistic season or core programs. While you might start with brochure content here, don't stop there. You want to think always from the standpoint of impact. What are the benefits to the community, artists, the art form, ties to education or multiculturalism in your program? How is this program a stretch for your organization, or the artists in your orchestra?

- Community Outreach/Education and/or Adjunct Programs--separately describe your audience development and outreach programs. Start with and update the descriptions of annual and recurring programs. Next add what is special and unique about this years programs and share details of one-time programs. Illustrate your content with examples and photos from last year's successful programs. Include participant's quotes. Their words are always going to include more weight than yours, no matter how hot-shot you think you are as a grantwriter!

- Organization--Who are the key players? Brief bios of artistic leadership and management here. Organizational challenges and triumphs. Any major projects in the coming year. (A Board List will accompany where appropriate).

- Financial Position of the Company--If you have a debt, here's where you explain it. If you have a surplus, here's where you explain why it is needed and why it can't be used for operating. Do you need to save to repair the roof next year, or are you on a cycle with a festival every two years? This is only a good news over-view, you'll need a detailed explanation for funders if you have serious explaining to do. (You'll attach financial statements where needed).

- In addition to your main project description prepare single sheets for specific adjunct and optional projects. Are you going to have two composers visit schools next year? Prepare a "Composers in the Classroom" page. Are you going to have musicians from your orchestra give workshops? Prepare a "Young performers workshops" page. Are amateur ensembles going to play before your concerts? Prepare a "Community Overtures" page.

- Update or create project pages from the former years projects. If you had a successful collaboration with a youth choir last season, do a one-sheeter on it.

- Try to keep your project titles consistent as that will allow you to send three sheets on "Young Artist Spotlight" that detail past and planned activities. Although the activities may have slightly different aspects, the one linking idea--in this example, young artists on the stage--will allow you to build a case for this stream of activity within your organization.

- Targetted foundation and corporate appeals

- Reports to donors on prior projects funded

- Fodder for larger applications

- To add to or tweak applications to foundations where added emphasis is needed to match the funder's priorities or mission.

- You can use MS Outlook, a database, or a spreadsheet to construct an annual calendar for you to chart the deadlines and progress of your grantwriting.

- Be sure to keep and include your accumulated knowledge arising from your past successes and failures with the funding body. Many funders ask you when you applied to them last, what for and what was the result.

- As you talk to officers, look at websites, add all information into your grant calendar listing. Link to application forms and guidelines where those exist.

- Where deadlines are given, you can enter those along with your own projections of when to schedule work on this grant. Many foundations will give vague information such as "meet before the end of each fiscal quarter". You will have to either find out the deadline or plan to have the application in well before the deadline might be anticipated to fall.

- You will determine patterns in your calendar which will allow you to schedule grantwriting weeks where you will lock the doors, turn off the phones for some part of the days and focus on a series of foundation appeals or a major operating grant. In my experience, given basic knowledge and writing skill, the major determiner of a successful grant is the time invested.

"Team, what team?" you ask. I smile as I have certainly written many grant applications on my own. However, there are ways to divide up the tasks to work with one or two other staff members in assembling materials for your more major grant applications. Even if it is only you on your lonesome, it may be helpful to you to think of working on your grant applications in terms of these tasks which may be extracted and assigned.

- Pre-read grant application forms, program guideline sheets AND final checklists, making a list of everything you will need for the grant. Please note that due to over-sight, omission or sadism, there will often be some item that you cannot get at the last minute which will only appear on one of three of these documents, usually the final checklist. If you only look at that as you prepare to mail your application, you will be up a creek without a paddle. Be sure you have defined the deadline properly: is it "postmarked by X date", "in our office before 5 pm on X date", or "in our office before midnight on X date".

- Solicit, acquire and create a file of all needed external and internal documents: These can depending on the program include: financial quotes on equipment you are intending to purchase with grant funds, artistic statements from artistic leaders, signed releases from creative partners, signed Motions of the Board authorizing the application, copies of Letters of Incorporation, signed Financial Statements, work samples on CD's, copies of scores, letters from references, marketing materials, marketing plans from companies on retainer, resumes of partners, etc. You will want to chart progress on these items to avoid nasty surprises.

- Create an electronic "fodder" file: On your computer network create a folder into which you throw copies of all documents likely to be of use to you during the grantwriting process. (You will delete these copies later). This will save you oodles of time in searching and opening and re-opening the same documents as you look for re-useable content. These documents will include your organizational profile, individual program sheets/descriptions. Strategic planning documents. Past grant application to the same government body. Recent grant application to other government bodies. Documents on financial planning. Statistics, budgets, and copies of marketing materials.

- Fill in grant cover sheet (get signatures done well in advance).

- Create separate documents for your main prose sections for the application.

- Cut and Paste--Use your current organizational profile and any other relevant content in your fodder file. Do a rough cut and paste of the material into the program sections where it best fits and might be helpful. Do not worry at this point about duplication. You are merely positioning the material for convenient accessibility.

- Statistics and Budget pages: Do these as fully as possible before starting on the prose. You can cut the time you spend on editing prose a lot more easily than truncating the time on stats sheets and Budgets. Trends evidenced in these sheets will help frame the prose.

- Write and edit. Self-explanatory as this seems, determine well in advance who the lead writer is and who gets to say, "this is done". Arguments on these points seem to happen frequently in mid-sized to larger organizations and make a tense process much worse.

- Proofread.

- Make the required number of copies and prepare as required

- Checklist of everything submitted

- Copy to file.

- Cover letter

- Mail, courier or hand-deliver. Nothing quite compares with the festive atmosphere in the line-up at the last post-office open in a major city on the deadline of a major grant. It is a time to meet old colleagues and catch up with the news from last year. But really, we'd much prefer to have been home at 5 pm rather than be in a post office at 10 minutes to 10 pm.

- Make a plan: List everything you want to tell the funder in brief points.

- Make it easy for them to give you the money by using their language. In addition to the application forms and guidelines that shape your writing, be sure to take time to read annual reports, strategic planning and online copy from your potential funding body. As you read, highlight (or electronically extract if possible) the prose in their documents that resonate powerfully with what you do or are proposing. Put this in your "fodder" file. Organizing your argument under sub-headings that echo their goals and priorities, using their language makes it easy for funders to see where your activities and plans fit their funding priorities. I worked with one great grantwriter who called this, "finding the money words".

- Tell your positive story first. Find several key points in each section that are strong positives. Put them upfront and in strong brief language. Use quotes from stakeholders, partners and leaders to enliven and add credibility.

- Address negatives briefly and honestly - move quickly to your positive plans (the only exception to this is applications for organizational effectiveness projects where you are making a case for the needs of your org.)

- Keep to length guidelines: Find out how flexible your funding body is in length guidelines. If they have some flexibility, don't abuse them. Sometimes copy from one question might be adapted and moved to another question that allows for a more lengthy response.

- Have you hit all your high notes? Look back at your list from No. 1. In your edits and moving blocks of copy around have you failed to tell some of your positive stories? See where you can fit those missed notes back in.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS:

- Be honest: Any dishonesty or misrepresentation in your application will assure you have a very short relationship with the funder, so you want to be sure that you'll deliver on everything you have outlined. Fudging on postage dates is mail fraud, unfair to your colleagues and creates a nasty, unethical climate in organizations where leaders coerce staff into going along with submitting applications days after deadline with an old postage meter label. Expose this where it occurs. If extensions are needed due to dire circumstances, often there is a way to submit a barebones application with additional material coming as updates.

- Don't forget to file your reports. A part of successful grantwriting is filing reports as required. Since you are reporting on last year's activities anyway, send reports even to those funders that don't require them.

- Recognize your funders: assure that funders have the logo recognition and thanks that meets or exceeds the funder's expectations. Forgetting the Canada Council logo on your program book today, means you will not want to send that program to them with your next application, no matter how good it looks. When logos and thanks are part of your development team plan, meeting your final requirements and giving courteous acknowledgement is assured