Wednesday, October 10, 2012

"I'm Not the Indian you are thinking about" at Harbourfront

Since I first worked with Sandra and Carlos at Red Sky in 2003 on "Caribou Song" while serving as General Manager at Soundstreams Canada, I have admired their choice in projects and their voice in Canada in dispelling stereotypes about native people.

There is actually a lot of vested interests on both sides in keeping those stereotypes alive but until we move past them we really can't have understanding nor begin to work together on the social justice problems that we'd all like to see addressed effectively.

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

Note to Factory Theatre Board: Please reinstate Ken Gass and stop the foolishness

I only came across this news (don't know how I missed it) when I saw Ken Gass's job posted on Work in Culture and wondered what the story was, had he retired, or whatever.

I just signed the petition in support of re-instating Ken. I first met Ken when I was a theatre student and a play I wrote was selected for one of Factory's reading nights at the old JCC. At one point I was shortlisted to work with him as General Manager at the theatre and we hit it off famously and stayed in touch. I regret that I didn't get the job but couldn't argue with the fact that I had only a small amount of experience with facility management and the building renovations were most important at that juncture. Whatever one thinks of his particular merits, there is a more important issue: Arts Boards in Toronto need to be told that the arts public does NOT want them to treat dedicated arts leaders and staff in this fashion. Arts organizations are not US corporations and we should not be sending our arts leaders to the door with their belongings in a shoebox.

Here's some press:

Change.org|How to Start a Petition

Tuesday, July 03, 2012

Delegation # 1: Why managers are afraid of delegating.

When you talk to unhappy employees and ask them what is wrong with their jobs or their relationship with managers, the leading issue is usually poor delegation techniques. In the arts and non-profits we are often working as managers having no business training in supervisory management and as employees we are working with bosses who may be wonderful in their fields but don't know the first thing about managing people.

Why do so many managers fear and avoid delegation?

# 1. Fear of loss of control.The inexperienced and insecure manager is afraid that if they don't do everything themselves things will spin out of control and they will lose authority to shape projects. Let's examine this fear:

- If you recognize this as your own fear as a manager, remember that you have the power to require employees to check in with you, report progress, and you can set the schedule for completion of stages in a project to build in time for edits and tweaks you feel are needed.

- Delegate from a sense of your own power and your fears will fade

# 2. Fear/Dislike of employees stealing credit or sharing the limelight.

Let's look hard at this fear:- Just as your organizations failures ultimately reflect on you as a manager, so do the successes

- A part of maturing as a manager and human being is learning to enjoy your new role as a mentor to a new crop of professionals. Their successes are your successes.

- If an employee truly tries to steal credit or becomes unduly competitive, that is a separate issue that you can deal with, ultimately you have the power to fire them so why be bothered by small expressions of ego?

#3. Don't feel you have time to teach employees how to do the delegated work or supervise them:

- If you are feeling time crunched, only effective delegation will get work off your desk so a small hump of extra work will pay off in the long run

- Part of delegating the task can be assigning the employee to job-shadow, read, take a course, do online tutorials to acquire skills. You don' t have to take on all the training yourself.

- While a lot of supervision might be needed the first time an employee takes on a job, it will decrease markedly the next time.

- Delegation and supervision IS your job as a manager. Likely all the work on your desk is really not your job and needs to be delegated.

#4 Worry that your employees will make mistakes, use methods you don't approve of, generally goof up something.

- Employees will make mistakes and that is a part of learning.

- Planning for training and supervision and scheduling to allow for error correction is part of your job as a manager and part of your effective delegation strategy.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Boundaries, clock-watching and values-based management

You need to leave on time for once because of family plans. It's busy at work and your boss says, "Well I don't know about you, but I've always been the sort of person who doesn't watch the clock at work because I prefer to just get the work done". It stings because your self-image has always been that of a hard-worker but there is nothing in the current situation or workplace that motivates you to stay late. What has changed? Is it you? Is it the job?

Getting to understand your own values helps to answer with confidence about the balance you have between commitments to work and to other parts of your life and what you need in order to give more time to work. As a manager, knowing your employees values helps you negotiate for the flexibility and extra effort you may need for a project.

Understanding what are core expectations for your position is the starting point. While you might have regular work hours, some contracts have language that requires a flexible schedule or extra hours in peak periods. It is only when we are asked to exceed the language in our agreement that we need to consider where our boundaries lie. While we like to give ourselves labels like "dedicated", healthy individuals have limits about the amount and type of work they are willing to do on their own time and the conditions under which they find it reasonable to put in extra hours. If you don't know your own priorities you could find yourself agreeing to work you'll resent or saying "no" to an opportunity that might be congruent with your goals. Neither of these outcomes is good for you or the workplace.

What motivates you to take work home, put in hours over the weekend, or stay late to finish a project? For me I know that I will volunteer to work on projects that involve learning new skills that are congruent with my goals and interests. I'll also burn the midnight oil for a project that I'm given ownership of that I can add to my resume folder in future. Affirmation goes a long way with me also. Even if there is nothing in it for me, I'll do extras when I feel appreciated.

As a manager, you need to know what your employees value and use that understanding to motivate appropriately. This is a part of values-based management.

- Employees motivated by financial security will go the extra mile for raises, promotions, contract renewal

- Employees with a thirst for learning will be motivated by staff training or time for taking on new work with steep learning curves

- Those with interests outside of work, family, hobbies, enjoying nature will be motivated by time-off in lieu of overtime hours

- Praise, recognition, and simple thank-yous motivate most of us, but are often the most neglected motivational tool in the management toolbox.

Friday, February 17, 2012

New animation from Prashant Miranda

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Writing Grant Proposals as a Team

Grantwriting in a Team Environment

Grants written with a collaborative team are usually stronger, more realistic and tied to the real activities and history of the organization and provide opportunities for team-building. Grants written with a collaborative team can also be among the most frustrating and time-wasting of activities if there is no plan for the collaboration and team members don’t adequately understand their roles.

Why write a grant collaboratively?- Capitalize on multiple talents

- Get multiple viewpoints

- Increase organizational and/or partnership buy in to the project proposal

- Define roles

- Choose the team

- Chart a realistic timeline

- Choose tools

TEAM ROLES:

NOTE: Many times one individual is responsible for more than one role in grantwriting, but it is useful to break down the roles to understand all areas of responsibility. For most grants the roles include:

1. The Grant Lead: This is the person, often referred to as “the grant developer” who is delegated responsibility for team leadership on the grant. They define the process, assign grant tasks, manage the timeline and are ultimately responsible for declaring when grant components are final. They may or may not be the actual grant-writer.

2. Grant Researcher: This role requires someone with skills and experience in researching funding bodies and (if applicable) expertise with the fundraising database used by your organization. They identify funding programs with high relevance to the activities of the organization.

3. The Grant Analyst: This role requires someone able to summarize the grant requirements and provide the information to key individuals within the organization for decision-making about whether and how to proceed and to set out key requirements needed to be met (such as signed contracts).

4. The Organizational Historian/Fact-checker: This role provides up to date content on organizational history, mission, projects, as well as needed documents such as board lists, audited financial statements, incorporation papers, photos, biographies/profiles of team members and partner organizations.

5. The Needs Manager/Project Rationale Researcher: This role is able to research the “need” that the project addresses whether it is a need in the community or an organizational need. Articulating the need is important to making a case for the relevance of your project (whether the application asks you to answer questions about needs or not).

6. The Grant Writer: This is the individual who takes all content provided and crafts it into a coherent argument that is presented with one voice through the document. They are ultimately responsible for style, grammar, format.

7. The Collaboration Organizer: This role is responsible for the nitty-gritty of the collaborative effort, sending invitations to team members, organizing meetings according to time-line, chasing people for content, and tracking the receipt of all needed materials, signatures, support letters, etc.

THE GRANTWRITING TEAM:

While above, I have defined the ROLES needed within a grant-writing process, one team member will likely assume more than one of the roles. Your grantwriting team may be 2 people or 20 people (or more). Most grants involve 2-4 key contributors with some input from stakeholders. Who you choose for your team depends on your organization and the nature of the application. While you typically would want only one person assigned to some roles (such as project leader and/or lead writer), others can be performed by teams (such as researching community needs or literature surveys, getting equipment quotes).

KEY SKILLS:

The skills you need to assure are on your team include:

1. A professional within the organization who has key insight in the organization’s history, goals, and able to speak to the nature and importance of the key points of the proposal.

2. A grantwriting professional who is skilled in researching funding opportunities in tune with organizational needs

3. A budget specialist able to craft a realistic project budget and answer financial questions about organizational finances

4. Writer/editor who will be the “voice” of the grant--responsible for the tone, grammar and persuasive language of the grant

Unless one person has ALL of the skills above, you need to develop a team however small! If you are the Grant Lead--taking into account both the roles needed in the grant and the list of key skills--consider who will make up your team. Following the rules for good delegation, you will need to assure that team members understand their role(s) on the team as well as the role of others. Each team member must have the tools and resources needed to perform the tasks (time, materials, budget) and the authority (existing or clearly delegated) to successfully fulfill their role.

TIMELINE:

Chart your timelines with key points for completion of stages of grant development through a work back schedule from the due date with full understanding of that due date which can vary from “postmarked by X date” to “must be in our hands by 5 pm on the due date”. While generally the earlier the better, a too early start date can undermine any sense of urgency about the work and lead to procrastination and dropped balls. Likewise some RFP have tight timelines that mean that intensive work will be unavoidable.

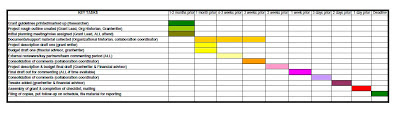

Generally the charting done by an experienced Grant Lead will look like this:

By making your first draft completion date far enough in advance, you can allow for a second round of commenting and revision if necessary or if the project gets behind schedule due to external factors or difficulties in obtaining all information needed, you can forgo this step.

TOOLS FOR COLLABORATION:

Do you need special tools for collaboration? Not necessarily. It depends on your team, process and proximity. If a grant is being written by one person who edits submitted content and incorporates 2-3 team members content and comments (the majority of grant-writing scenarios) no special tools are needed. Emails, word documents or notes written on a table napkin, will all be incorporated by one individual into a master document that is not available for editing by anyone else. No tools beyond a word processor needed.

Where it gets dicey is where multiple individuals are working on writing/editing sections of the grant collaboratively (and there has to be a strong rationale for this approach). Here version management becomes difficult and if there is no system in place, valuable content can be erased by a contributor who lacks the big picture. The grantwriter has started by organizing content into paragraphs dedicated to single ideas, ensuring that all building blocks are in place over the entirety of the grant. This can become lost as new writers add irrelevant details to paragraphs unaware those ideas are stated later, or in a different section of the application that they may not have in front of them. Simply tracking the revisions becomes a chore. Take this as an example: Susan has written the first draft of a project timeline that outlines a series of workshops. She sends it out simultaneously to Sandra and Kevin by email. Sandra gets back to Susan first with her revision and has added 2 workshops to the list. Kevin (working on the original document) adds one workshop. If Susan saves the most recent edit (Kevin’s) as final, she will not have incorporated Sandra’s input. So how will this be avoided without adding hours of pouring over revisions with a fine tooth-comb?

The need for a unified voice and coherence within the full application dictates that:

- The process for editing needs to be clearly articulated

- There needs to be a start and end point to edits (a date where no more edits will be received and the key writer will consolidate).

- A system or tool for tracking versions must be decided on and used by all contributers

- The final edit must be done by one person assuring a single voice and coherent thread.

MS Word “Track Changes”:

When two or three editors work on a document and only one or two revisions are anticipated, the tools within Word for tracking changes, emailed back and forth will likely be sufficient to the team’s needs, provided they agree on version labeling and documents are not sent to multiple editors at one time without the knowledge of the key writer. The key writer needs to know which version of the document the edit is based on to not lose content previously submitted.

The drawback of “track changes” with multiple edits and editors is that the document becomes unreadable unless the revisions are hidden by selecting “show final”, however in that view content crossed out by one editor which may be necessary and need to be restored can be lost.

Google Docs

Google docs are similar to MS Word’s track changes in look and feel. The advantage of using Google docs is that two people cannot work on the document at the same time so that the most recently saved document is always based upon the work of all previous contributors.

Wikis

Wikis were developed specifically for collaborative writing and allow team-members to look at all version histories. Within a wiki, it is easy to roll back to a prior version or ensure content is not lost. There are a number of free wiki spaces available online and using wiki tools are highly recommended where team-writing for sections of a grant involve three or more people and or is anticipated to involve more than two rounds of editing. My favorite wiki spaces include: http://www.wikispaces.com/ and http://pbworks.com/

Proximity (a collaborative tool we sometimes forget):

Grant-writing teams seldom go off the rails when collaborators work in the same office space and work the same days/shifts. When they do not, it is important to be able to simulate the good synergy effects of proximity. Wiki tools help with this. Meetings, web conferencing, shared Skype calls, and even meeting virtually in online environments can avoid the pitfalls that occur when collaborators feel they are working in a vacuum at some points and are surprised by input from other team members at other points.

Symptoms of failed collaborative grantwriting:

Reluctance to contribute in a timely fashion: One of the leading signs of a process that is failing is the hording of information and avoidance of content sharing until the last moment of a grant deadline. People do this as a defense when they feel that earlier input will be lost or be subject to so many revisions that it will add to the time they will actually be required to spend on grant-writing. "Why contribute now, it will only have to re-done 10 times?"

Lost or confused content: Editors are simultaneously working on the same document making tracking versions difficult to impossible. "I'm sure we had something in here about X in an earlier version. Where did it go?" The wrong tools are being used for collaborative writing.

Surprises and conflicts: "Why are you working on X? I've already done it!" The team and roles were not clearly defined.

Loss of engagement by project and/or writing lead: You send your lead writer comments and edits galore and they stop responding. There's likely a timeline problem. The editing process needs to have a clear end-point so that final draft can be constructed. Grantwriters who are unsure of when they are needed for final edits may be reluctant to contribute until they are sure the dust has settled to avoid wasting their time.

Lack of consistent voice and format in final grant: Editing and commenting has not been terminated with enough time for grantwriter to polish and format or grantwriter has not been correctly delegated authority to override edits that are off message.

Lastly take this quiz

- We always have organizational buy-in for our grant-writing before we begin. Yes/No

- Our grant team all know their own roles and responsibilities. Yes/No

- All team members know from the outset who will contributing and how. Yes/No

- Our grant process has a defined time-line for key steps. Yes/No

- Our tools match the number of collaborators we are involving. Yes/No

- We work in close proximity or have plans for meeting/conferencing as needed. Yes/No

- We have no difficulty tracking revisions to grants. Yes/No

- We are never surprised at the last minute by missing documentation or signatures. Yes/No

- Team members contribute on schedule with confidence their input will not be lost. Yes/No

- Grant proposals have a unified voice and a coherent argument on completion. Yes/No

SCORING:

Give yourself a point for all your “yes” answers.

A perfect 10: Where do I apply to work for you as a grant-writer? Great going.

7 to 9: You are like most organizations, doing most things correctly but there’s probably just one area where you could avoid conflict and time wasting if you planned a little better.

4 to 6: You are probably experiencing some staff stress or even conflict. You may be wasting time and energy due to duplication of work by people not understanding their roles and/or doing intensive last-minute grant-writing due to lack of pacing.

Less than 4: Grant-writing collaboratively is either very new to your organization or has become a huge trial that your staff members view with dread. They react with either avoidance/delay strategies or by jockeying for position when a grant-writing task is announced. The process is likely always contentious and the results are worse than if one person completes the grant leading you to feel it is better you do it yourself. (Most of us have been there.) Consider, if you feel this way, whether your team really lacks the skills or whether the process is at fault.